In 1993, utterly out of the blue, the Austrian pianist Paul Badura-Skoda was despatched a photocopy of a manuscript purporting to be six misplaced Haydn keyboard sonatas. It got here with a letter from a little-known flautist from Münster, Germany known as Winfried Michel, who informed Badura-Skoda that he’d been given it by an aged woman whose identification he couldn’t reveal.

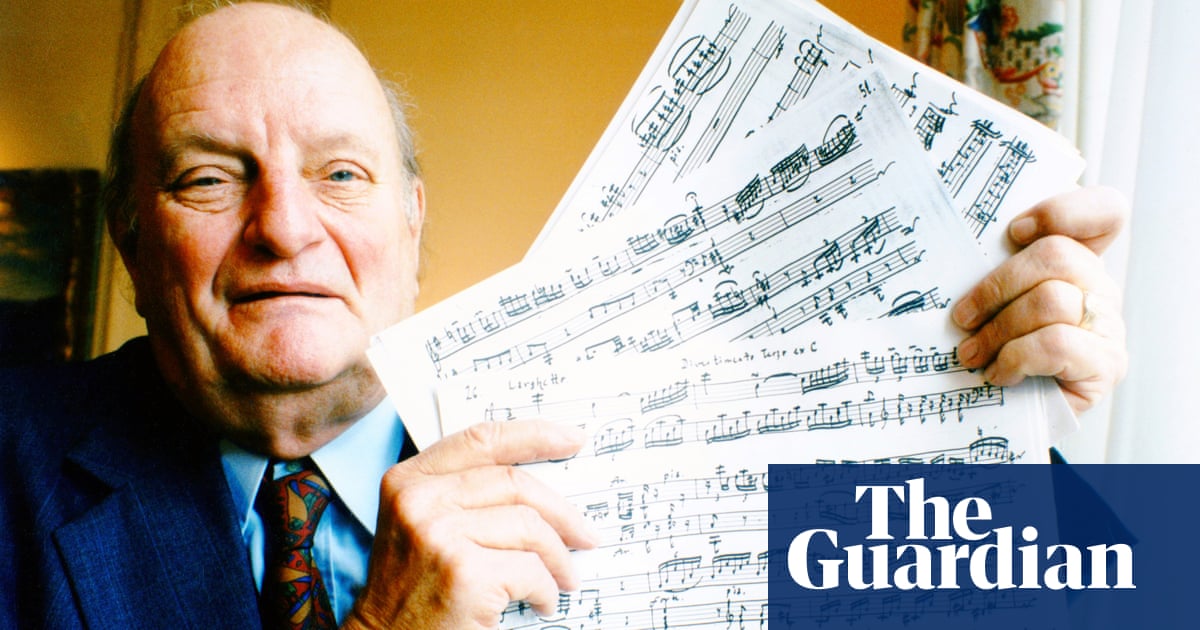

Badura-Skoda was suspicious, however as soon as he performed the music, he grew to become positive that the works have been actual. He requested his spouse Eva, a musicologist, to look at the manuscript. Though the music wasn’t in Haydn’s hand, she believed it to be an genuine copyist’s rating relationship from round 1805 and originating in Italy. They checked with the Haydn scholar, HC Robbins Landon, and he too was satisfied. He penned an article for BBC Music Journal, headlined Haydn Scoop of the Century, tipped off the Instances, and known as a press convention for 14 December 1993.

Inside hours, the Joseph Haydn Institute in Cologne declared the manuscript to be a faux. An knowledgeable from Sotheby’s in London agreed. The Badura-Skodas had been hoaxed, or so it appeared. The next February, Eva gave a chat in California titled: The Haydn Sonatas: A Intelligent Forgery. Paul performed a number of the works – in a confused mind-set. Eva informed the music scholar Michael Beckerman, reporting for the New York Instances, “My husband nonetheless thinks they’re real,” elevating tough questions on fact and artwork. What did Paul consider he was taking part in? What was the viewers listening to? And did it matter?

In his article, Beckerman wrote: “Realizing {that a} work is by Haydn or Mozart permits us to see ‘inevitable’ connections. Take away the understanding of authorship, and it’s devilishly tough to learn the musical photos inside.” He famous, too, that it was the inauthenticity of the manuscript that had uncovered Michel and never the constancy of the music. And so, Beckerman dared to ask: “If somebody can write items that may be mistaken for Haydn, what’s so particular about Haydn?”

Does Beckerman assume there’s a lot to attract from the story of the misplaced Haydn sonatas if we think about it right now? “I believe it pushes us to query what it’s that we all know,” he says. “How will we come to realize it? After which how will we specific it to others? And, specifically, how will we specific it to others who may not agree with us? I believe these questions are nonetheless utterly apropos, and this sort of forgery pushes us to maintain asking these questions and never fake to know stuff that we actually don’t know.”

What makes one thing a truth? Within the catalogue of their works, the Milan-based music writer Ricordi lists the well-known Adagio in G Minor – a staple of movie scores, together with Gallipoli, Rollerball and Manchester by the Sea – as being by the Italian baroque composer Tomaso Albinoni, however elaborated upon by a musicologist known as Remo Giazotto. Giazotto claimed that he accomplished the work within the late Nineteen Forties from a fraction of Albinoni’s precise music – a bassline and two quick melody elements. However because the Albinoni knowledgeable Michael Talbot tells me: “Giazotto by no means supplied any passable rationalization or description of the supply from which he took the fragment. My view is that it’s an authentic composition.”

Ricordi first printed the work in 1958. I requested why they proceed to record it as being no less than partially composed by Albinoni when the connection can’t be proved they usually didn’t reply. However the issue for any sleuth that examines the case of Adagio in G Minor is that its reference to Albinoni can’t be comprehensively disproved. Not like with the Haydn sonatas, there isn’t any authentic manuscript for specialists to discredit, solely proof collected by the likes of Talbot pointing to the probability that it by no means existed.

Giazotto, who died in 1998, by no means owned as much as his suspected hoax. After his manuscript was rubbished, Winfried Michel known as the Haydn sonatas “completions”, with out explaining what he meant. It will take till 2022, three years after Paul Badura-Skoda died, for him lastly to confide in a newspaper in Münster that he had composed the works, impressed by the incipits – their real opening 4 bars, which had survived in a list of Haydn’s works. There was a mattress of fact on which to sow the seeds of very tall story, as there was within the unusual case of Joyce Hatto, the English pianist who loved a late-life detonation of success within the early 2000s. Her husband, a file producer known as William Barrington-Coupe, palmed off greater than 100 CDs of different pianist’s performances as her personal whereas she was sick with most cancers, fooling critics. If Hatto hadn’t had an precise profession between the Fifties and Seventies, the hoax would by no means have been plausible. She died in 2006, a yr earlier than the ruse was uncovered, leading to many Hatto obituaries remaining on-line – together with on this web site – which might be a discombobulating mixture of fact and nonsense.

Musical hoaxes power us to query not simply authenticity and methods of understanding, but additionally how we outline phrases. In 2014, the supposedly deaf composer Mamoru Samuragochi surprised Japan when he confessed to utilizing a ghostwriter for the 18 years by which he’d turn into well-known for writing video-game scores and conventional classical music, together with a symphony devoted to the victims of the bombing of Hiroshima, his dwelling metropolis. He additionally wasn’t legally deaf. The ghostwriter, Takashi Niigaki, labored to Samuragochi’s briefs. How will we outline a composer in that equation? And who was the artist? The story is wealthy with irony; after the hoax was uncovered, Samuragochi grew to become a recluse, Niigaki a public determine. “It was like Samuragochi had the temperament of an artist, however lacked the instruments to truly create artwork,” wrote Christopher Beam in The New Republic. “The closest he got here to a masterpiece was the efficiency itself: the mass duping of a nation that uncovered its personal goals and vulnerabilities.”

In a 2013 guide, Solid: Why Fakes are the Nice Artwork of Our Age, Jonathon Keats wrote, “Artwork forgery provokes nervousness.” He was referring to fine-art, however maybe his views apply right here. “As a result of artwork is a uncommon refuge from the mass-produced inauthenticity of the industrialised world, we’re hypersensitive to any risk to the authenticity of artwork.” As such, he added, “No genuine fashionable masterpiece is as provocative as an awesome forgery. Forgers are the foremost artists of our age.”

Allow them to additionally act as admonishers. A forger makes mincemeat of established narratives and gnaws on the rootstock of perception methods that shouldn’t be taken as a right. There’s artwork within the con, but additionally a warning.

Supply hyperlink