On a current Saturday at an auditorium in Nairobi, a rapt viewers of greater than 600 individuals held their breath because the revered Kenyan statesman and independence activist Tom Mboya walked out of a pharmacy together with his good friend Mohini Sehmi.

Gunshots rang out. “Did you hear that?” a panicked Sehmi requested Mboya, who slowly collapsed to the bottom. “Tom! Tom! Tom!” she referred to as frantically, realising that he had been hit.

The scene is a part of a play that captures Kenya’s transition to independence by the extraordinary lifetime of Mboya, who, amongst different issues, was a strident campaigner in opposition to authorities corruption earlier than his premature loss of life in a suspected political assassination on the age of 38. It’s one instalment of a wider sequence retelling Kenya’s historical past referred to as Too Early for Birds (TEFB), first carried out in 2017.

Viewers participation is inspired, and amid the oohing and ahhing and booing and laughing there are occasional shouts of a phrase that brings the previous instantly into the current: “Ruto should go.”

Kenya has been roiled in current months by the deaths and abductions of individuals accused of involvement in a sequence of mass anti-government protests. These started on 18 June in opposition to proposed tax rises however broadened to embody wider requires reform, partly in response to the way in which the preliminary demonstrations had been violently suppressed. Lots of these current chanted for the resignation of the president, William Ruto.

On prime of the dozens of individuals killed through the protests, scores extra had been forcibly kidnapped or went lacking. Between June and December, 82 instances of enforced disappearances had been recorded by the Kenya nationwide fee on human rights. A few of these declared lacking have resurfaced alive. Others have both been discovered lifeless or not discovered in any respect.

The protests constituted the largest disaster in Ruto’s presidency. He ultimately scrapped the finance invoice that contained the proposed tax rises and sacked virtually all of his cupboard in an try to convey the state of affairs below management, all whereas dismissing stories of police abductions.

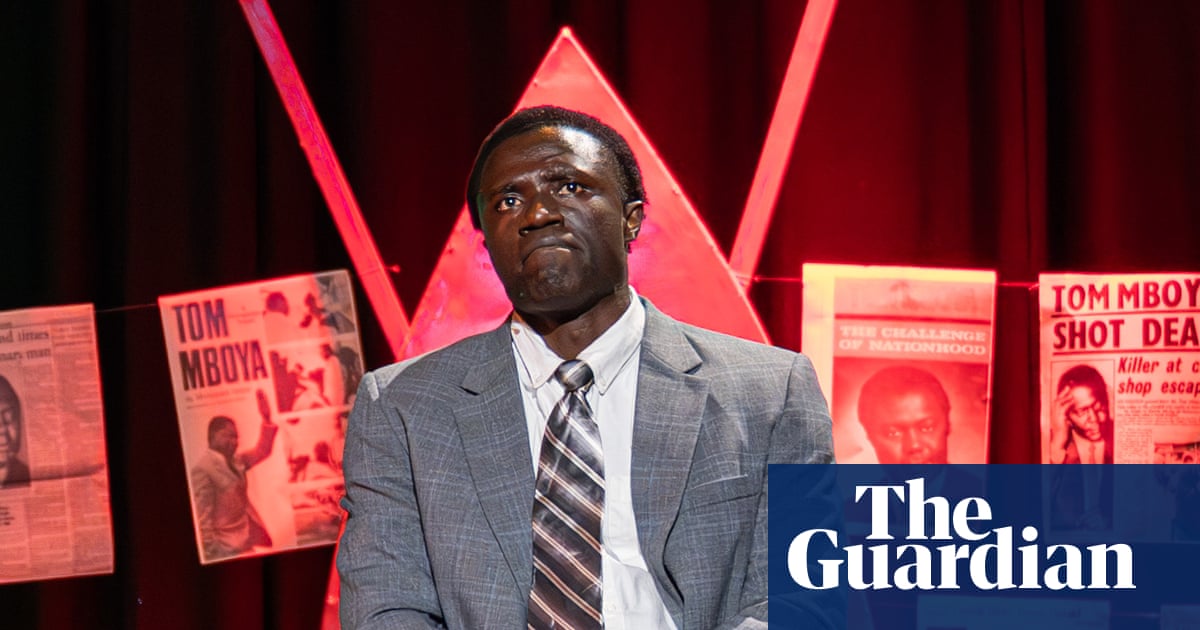

{Photograph}: Edwin Ndeke/The Guardian

Since September the road demonstrations have slowed down, however the wave of killings and abductions – and related anger in the direction of the police and the federal government – has continued.

“A whole lot of the occasions that we describe in Mboya are nonetheless occurring virtually in the very same manner right this moment,” mentioned Mugambi Nthiga, the play’s director and co-writer. “It was obligatory to indicate people who solely the calendar time has modified. You continue to have an previous guard that advantages from oppressing, disenfranchising and stealing from the most important populace, and younger individuals must stand up and current another.”

The play spans Mboya’s total life, from his childhood on a colonial farm to his loss of life exterior a pharmacy in Nairobi in 1969. Having risen to political energy by main negotiations for independence in opposition to the British at Lancaster Home, he went on to construct Kenya’s commerce union motion, begin a programme to ship Kenyans to American universities, and far more apart from. He was minister for financial planning and improvement on the time of his loss of life.

The newest manufacturing of Tom Mboya is only one of a sequence of current stage exhibits that supply audiences the chance to attract parallels between historic and present-day occasions. Others embody the musicals Dedan Kimathi, concerning the eponymous Kenyan freedom fighter, and Sarafina!, about opposition to apartheid in South Africa.

Abu Sense, co-creator of TEFB and an actor within the Tom Mboya play, mentioned: “It’s virtually as if we’re making Kenya into a personality and giving it a persona, [allowing audiences] to know the place Kenya got here from and the way we’re supposed to maneuver ahead.”

Ngartia, one other TEFB co-creator and actor, mentioned Mboya’s rise from an extraordinary childhood and the truth that he had character flaws similar to anybody else make him a potent set off for the notion that people can impact change or, as Ngartia put it: “I don’t need to be excellent to take part.”

“There isn’t a superman,” he added, quoting a line from the play. “It doesn’t take one man to show the conscience of a nation … We truly need to go on the market and eat that teargas ourselves.”

Gathoni Kimuyu, the inventive director of TEFB, mentioned the similarities between Mboya’s impactful rise as a younger man and the present-day accountability motion being pushed by individuals of their 20s exhibits “we’re not removed from what our historical past is”.

“I hope it makes the youthful technology realise that the issues Mboya did and dreamed of are additionally of their attain,” she added.

Beldine Moturi, a 25-year-old software program engineer, mentioned after watching the play that it had taught her the significance of “decentralising revolution [from] round one particular person” and that everyone has to play a job to vary a rustic’s course. “It’s everybody, as we’re seeing with the protests,” she mentioned. “It’s every particular person taking their half and doing their half.”

TEFB is constructing on a physique of Kenyan political theatre that goes again to the Seventies with author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s Kamiriithu theatre group, which staged performs depicting the brutality of the British colonial administration and critiquing the administration of impartial Kenya. The federal government ultimately banned the group.

“What we’re doing – scene by scene, story by story, laughter by laughter, tear by tear – is therapeutic bits of this widespread physique we name a nation,” mentioned Ngartia.

Within the play’s closing scene, the Mboya character, performed by Xavier Ywaya , reappears and walks to the entrance of the stage. “We’ve a proper to be free,” he says. “We’ve all the time had the proper.”

Supply hyperlink