Donald Trump has picked former soccer participant Scott Turner to steer the U.S. Division of Housing and City Improvement. Whereas not a lot is thought about Turner’s positions as he awaits affirmation by the Senate, Trump’s choice attracts consideration to the incoming administration’s housing insurance policies.

These insurance policies, evident in each the primary Trump presidency and in feedback made throughout the marketing campaign, counsel an abiding religion within the personal sector and native authorities. And they’re more likely to embrace deregulation and tax breaks for funding in distressed areas.

Additionally they present a disdain for federal truthful housing packages. These packages, Trump mentioned on the marketing campaign path in 2020, are “bringing who is aware of into your suburbs, so your communities shall be unsafe and your housing values will go down.”

‘Inharmonious neighbors’

In his September 2024 debate with Kamala Harris, Trump responded to a query on immigration by amplifying the discredited rumor that Haitian immigrants in Ohio had been “consuming the pets of the folks that dwell there.”

“That is what’s occurring in our nation,” he added, “and it’s a disgrace.”

As a historian of public coverage centered on city inequality, I’m struck by the similarity between Trump’s diatribe and the beliefs that instituted racial segregation in housing a century in the past.

Trump’s false declare echoes the long-standing anxieties of white householders concerning immigration typically and African American migration particularly.

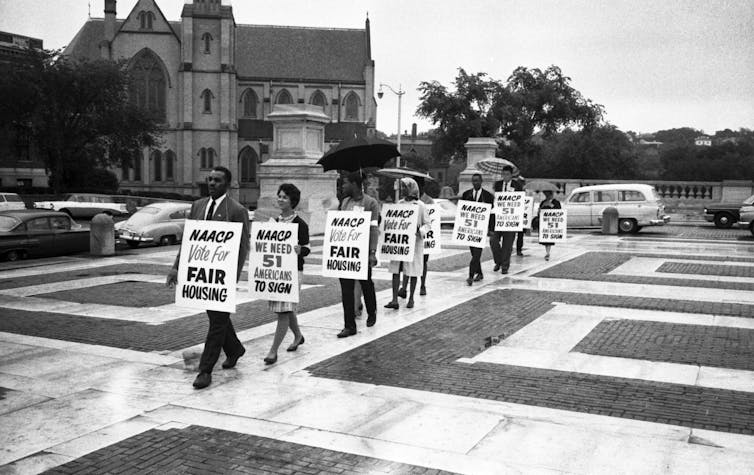

AP Photograph/Luis Andres Henao

Each circumstances pit the pursuits of 1 set of residents towards these of one other.

First, there are the established, overwhelmingly white, residents – in Trump’s lingo, “the folks that dwell there.” Then come the undesirable new arrivals whose sudden presence in American neighborhoods is seen as a menace to public well being, welfare and property values.

Traditionally, the threats posed by “inharmonious” neighbors – as actual property brokers and later federal housing companies put it – have centered on immigrants and African People.

The surge in immigration to the U.S. on the finish of the nineteenth century animated a notoriously nativist response from native governments and realty teams. It included early efforts at land-use zoning aimed toward establishing economically and racially unique residential districts in cities. And it concerned the primary stirrings of white flight to the suburbs, particularly within the quickly urbanizing Northeast and Midwest.

Patchwork apartheid

But it surely was the Nice Migration of African People within the first many years of the twentieth century, coupled with the city residential increase of the Twenties, that galvanized the peculiarly American alchemy of race and property.

Throughout this era, many cities, starting with Baltimore in 1910, experimented with explicitly racial zoning that designated neighborhoods for solely white or Black occupancy.

The Supreme Courtroom struck these legal guidelines down in 1917 on the grounds that it invaded “the civil proper to accumulate, get pleasure from and use property.”

With the choice of legally codified racial zoning closed, as I element in my guide, “Patchwork Apartheid,” the white response to the Nice Migration turned to the personal and piecemeal motion of builders, actual property brokers and householders.

The centerpiece was the widespread use of personal contracts designed to forestall these “not wholly of the Caucasian race” from proudly owning or occupying houses in “protected” neighborhoods.

This personal resistance to built-in neighborhoods was occurring as new housing begins ballooned after the conflict, from 240,000 a 12 months in 1920 to nearly 1 million in 1925.

These restrictions took quite a lot of kinds.

Suburban builders generally imposed prohibitions on African American occupancy or possession of latest development, particularly within the quickly rising cities of the Midwest. Present residents of older neighborhoods going through racial transition in locations similar to Chicago and St. Louis would additionally impose racial covenants by petition.

In all these settings, as I element in my guide, racial restrictions had been routinely connected to particular person house gross sales by patrons, sellers or actual property brokers. They hoped to thrust back what white realty pursuits routinely known as “invasion” or “encroachment.”

The consequence was a form of patchwork apartheid. It was crafted nationwide however stitched collectively parcel by parcel, block by block, subdivision by subdivision.

Stark racial segregation

My work on St. Louis has uncovered nearly 2,000 racially restrictive agreements imposed between 1900 and 1950. By 1950, this patchwork of personal restriction encompassed practically two-thirds of the St. Louis area’s residential properties.

Their core logic was that occupancy by inharmonious neighbors constituted a “nuisance” use of property.

Earlier than 1920, personal property restrictions generally included a basic nuisance provision barring business makes use of, usually itemizing trades offensive to the senses, similar to a slaughterhouse or a junkyard, or to 1’s morals, similar to a tavern.

In response to the Nice Migration, white realty companies in St. Louis and elsewhere merely appended “coloured” occupancy to their listing of nuisances.

For instance, the uniform settlement utilized by the St. Louis Actual Property Change banned two lessons of patrons or renters: “any slaughterhouse, junkshop, or rag-picking institution” and “a Negro or Negroes.”

Within the St. Louis subdivision of Cleveland Heights, an extended listing of proscribed nuisances was capped with the availability that no lot may “in any manner or method” be “occupied by any individuals apart from these of the Caucasian Race.”

Some restrictions elided racial classes and nuisances by limiting gross sales to residents thought-about merely “objectionable” or “undesirable.”

A standard clause present in most Midwestern settings barred any “race or nationality apart from these for whom the premises are meant.”

Such personal restrictions had been dominated an unenforceable violation of equal safety by the Supreme Courtroom in 1948. And so they had been prohibited outright by the Truthful Housing Act 20 years later.

However the injury – stark racial segregation and a yawning racial wealth hole – was executed. And the core assumptions about race and property lived on within the insurance policies of personal realty, lending and appraisal.

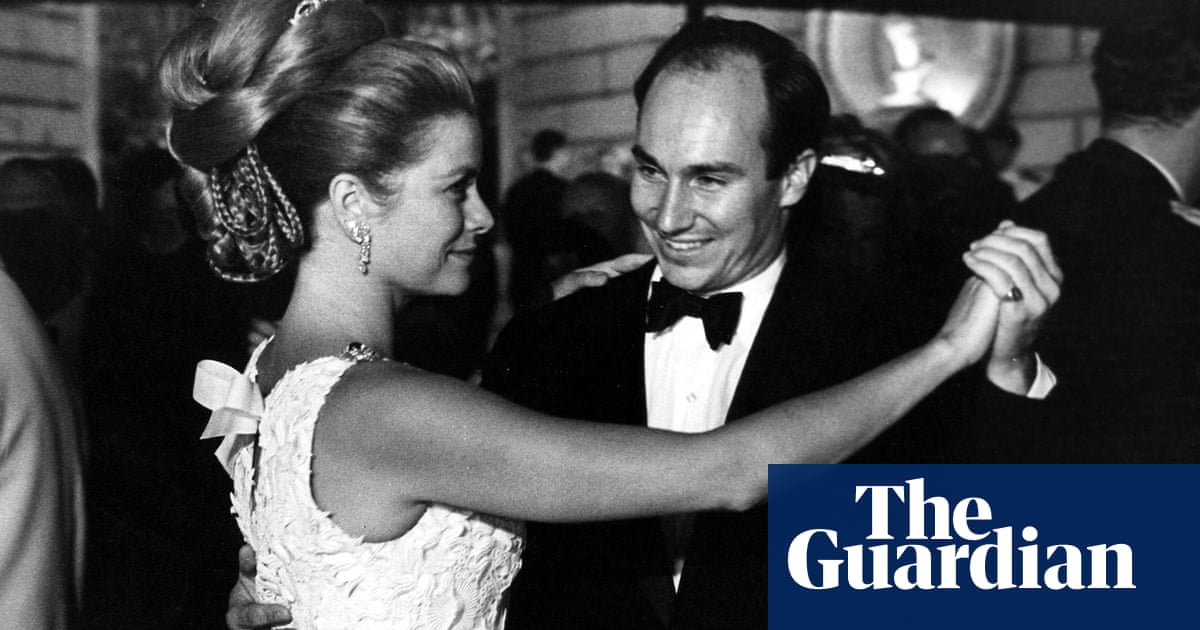

Photograph by Bettmann Archive/Getty Pictures

‘Your communities shall be unsafe’

Trump’s debate outburst, on this respect, mirrored a racial politics formed as a lot by his actual property background as his political aspirations.

Trump inherited a property portfolio from his father that was already deeply dedicated to racial segregation and discrimination towards African American tenants. Starting within the Seventies, his household’s New York realty follow was infamous, and routinely sued, for violations of the 1968 Truthful Housing Act, meant to verify personal discrimination in personal realty.

As president, Trump continued to erode the notion of truthful housing for all.

In 2020, he jettisoned an Obama-era rule requiring that cities receiving federal housing funds affirmatively handle native discrimination and segregation.

“The suburb destruction,” he promised on the time, “will finish with us.”

Trump housing 2.0

Turner, as the following HUD secretary, is poised to select up the place the primary Trump administration left off.

Think about the housing agenda of Venture 2025, the Heritage Basis’s sweeping blueprint for the second Trump administration. Penned by Ben Carson, Trump’s first HUD secretary, it proposes a radical retreat from federal “overreach” that would come with gutting anti-discrimination provisions in federal packages and deferring to localities on zoning.

It could additionally bar noncitizens from public housing and reverse “all actions taken by the Biden Administration to advance progressive ideology.”

On the time of Trump’s Springfield, Ohio, feedback, the apocryphal specter of pet-eating immigrants appeared however yet another oddity in a marketing campaign punctuated with them.

But it surely was greater than that. It was the preamble to a brand new chapter within the U.S.’s lengthy historical past of discriminatory neighborhood “restriction” or “safety.”

Supply hyperlink