Look round you and earlier than too lengthy you might be prone to spot a chore jacket. I noticed a very wonderful instance on a dad final weekend at a heritage railway. As heat days stretch into still-cold evenings, beer gardens are filled with them. They’re worn down allotments and in cities, and I’ve a couple of in my very own wardrobe. As a result of what started as on a regular basis workwear for French manufacturing unit workers greater than a century in the past has immediately develop into a wardrobe stalwart. You may even discover chore jackets within the grocery store, with Sainsbury’s Tu and Asda’s George providing the most affordable – the easy design lends itself to mass manufacturing.

They march throughout my Instagram feed, from workwear-inspired manufacturers LF Markey, Folks or Uskees, down by means of excessive avenue shops comparable to Zara and John Lewis, in addition to at hyper-expensive label The Row – your French machinist might need muttered a piquant “dis donc!” at its chore, with pockets too shut collectively and a £1,500 price ticket. The jacket has been worn by the likes of Brooklyn Beckham and Hailey Bieber, whereas Harry Types is usually seen in a model by SS Daley, the label impressed by British class tensions (and during which he has a monetary stake).

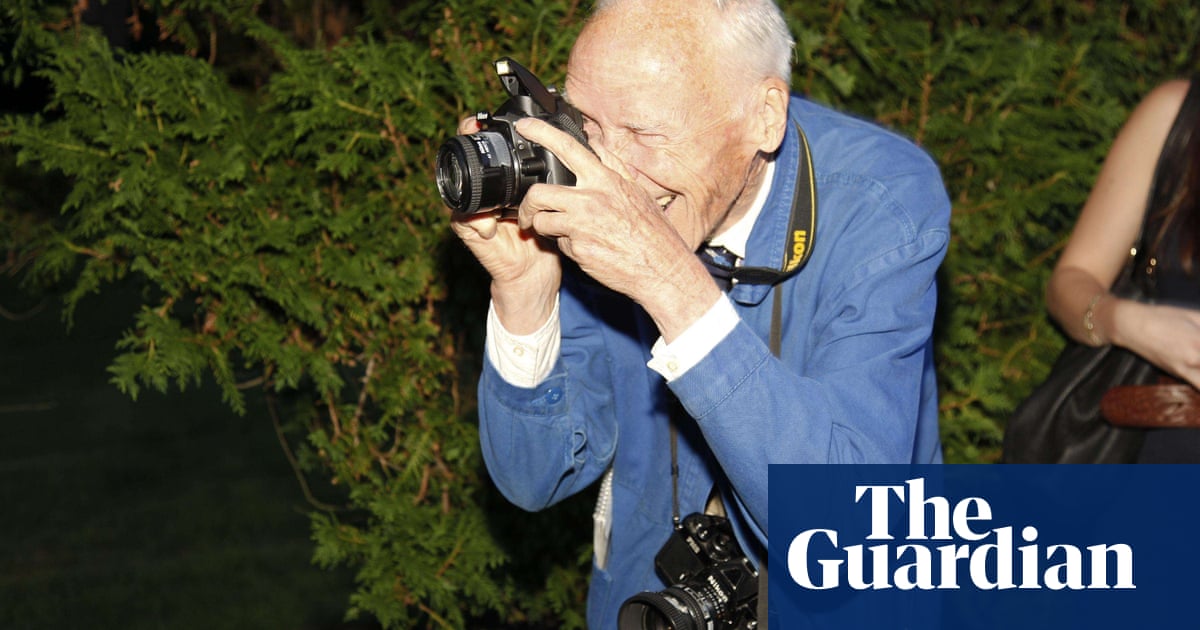

So how did we get right here? Conventional homeware retailer Labour and Wait began promoting a jacket by old-school French model Mont St Michel when it opened in 2000. However the coat arguably discovered its strategy to up to date style by means of New York avenue model photographer Invoice Cunningham, who wore one like a uniform as anybody who watched a 2010 documentary about his life and work properly is aware of. Monty Don embraced its purposeful origins by carrying one within the backyard, even inspiring a Reddit thread the place contributors ask “how can I costume like Monty Don?”. On the shoulders of those sensible and inventive males, the chore coat developed from its utilitarian origins.

Different designers have since gone rogue with the traditional model, with blended outcomes: the Tate is promoting a chore made in collaboration with London streetwear model Lazy Oaf, in brilliant indigo with garish embroidered particulars. Adidas’s “chore” is a burgundy jacket with the sportswear model’s emblem on the again, fixed with zips and Velcro. It’s completely hideous. Even brewers are getting in on it, with Guinness launching a collab with Native Jeans: its off-white physique with darkish buttons is maybe imagined to replicate the colouring of their fiendishly well-liked pints, however as an alternative seems to be like white cloth that has been washed with black socks.

Many of those outliers are removed from the unique. So what is a real chore? I assumed I had two, each classic: a blue cotton jacket and a heavy brown canvas railway employee’s coat with a Peter Pan collar. Apparently not, in accordance with Marie Remy of The French Workwear Firm, who has been promoting the coats since 2014. Her father, a mechanic, wore the bleu de travail (as they’re recognized in her homeland) to work six days every week. Remy is a purist and for her, the bleu needs to be made out of blue cotton twill or moleskin and have three patch pockets: two giant ones and a smaller one increased on the breast. It ought to “completely not” have a lapel collar (like mine) however rise as much as the neck with 4, 5 or, at a push, six buttons.

The jacket’s roomy, boxy form makes it each sensible within the office (there’s no free materials to get caught in equipment) and adaptable in model. “In case you bought a toddler to attract a jacket, it will be virtually like workwear in the way it’s pared down,” says Remy. “That’s why I believe it survived so lengthy.”

An skilled within the historical past of the coats, she explains that they took off after the primary world struggle, when the speedy industrialisation of France led to extra factories, an employment increase and, considerably, collective bargaining energy. The rights negotiated by French unions included free clothes for his or her workforce, with some males at firms comparable to SNCF or Gaz de France entitled to not less than one new chore coat annually. This led to the overproduction that Remy believes explains why they continue to be so plentiful on the classic market immediately. “In some sectors, the unions would even handle to barter the prices of washing the clothes,” she says. “You need to consider the clothes as work instruments, actually.”

after publication promotion

Common, usually intensive, put on meant that every jacket turned distinctive, taking over the imprint of its proprietor’s life and labour, and this has fed into their trendy attraction. Fergus Henderson, co-founder of the London restaurant St John, is such a fan that he and enterprise accomplice Trevor Gulliver collaborated on their very own chore with Savile Row-based menswear model Drakes. In keeping with Gulliver, Henderson refers to his authentic French jacket “as his historical past, a type of diary of days” – each crease or stain tells a narrative. He praises the chore for “sturdiness, an everyman high quality, and they’re merely of sound design – they work”.

However the reputation, and even the fetishisation, of workwear might be thorny. Within the case of the chore, the fashionable center class has plucked them from their historic context, whereas concurrently having fun with the authenticity they sign by dint of their blue-collar origins. (In spite of everything, we get the time period “blue collar” from workwear, since blue dye was the most affordable accessible for these mass-produced gadgets.) The truth that they exist because of the hard-won rights of the early-Twentieth-century French unions, and the graft of those that spent their total working lives in them, arguably turns into a type of ironic appropriation if you happen to’re carrying one to the native farmers’ market to drop a tenner on kimchi.

Modern designers are conscious they now sign a sure id. “In case you recognise your self as any individual that doesn’t essentially sit behind a desk, then the chore coat is for you,” says Erica Toogood, sample cutter on the eponymous model she based along with her sister Faye. The chore was a direct inspiration for his or her mechanic jacket, which stays a staple of the gathering they launched in 2013.

“One of the lovely issues is the thought of the chore coat being for the nameless employee, but each a type of classic jackets signifies the DNA of the person who’s worn it,” she says. Her problem as a sample cutter is to echo this sense of a private historical past, even in a brand new garment. “We attempt to lower these parts in to point out that perhaps any individual has been in that jacket earlier than you, and that you simply’re merely taking over the position of wearer as one other particular person alongside the road.”

Remy believes that classic chore coats stay well-liked due to their sturdiness. “Individuals are drawn to them as a result of it’s like a backlash towards quick style,” she says. “What are you able to do as a person? It may really feel overwhelming, it’s very troublesome.” To her, shopping for a chore coat is “a mini standing as much as it as a person. It’s connected to values.”

One sure-fire means up to date designers can construct positively on the jacket’s historical past is making new ones in bigger sizes – we’ve all bought quite a bit larger for the reason that early Twentieth century. This has been on the core of the Toogood philosophy, which as a unisex model has a common sizing vary.

Regardless of the abundance of chore coats available on the market, familiarity doesn’t must breed contempt. When the chore is finished properly, and doesn’t stray too removed from the unique mannequin, it stays versatile and cozy, whether or not a battered 60-year-old classic jacket or a brand new, dearer, long-term funding. For Toogood, “they develop into agency pals that keep in your wardrobe for years”.

Supply hyperlink