Many of the formative movies of my childhood include crisp sense reminiscences of the primary time I noticed them: exactly what cinema or whose sofa, the time of day and the climate outdoors, who I used to be watching with, my in-the-moment reactions to what delights or shocks the movie threw at me.

The Sound of Music, nevertheless, is an exception. Robert Smart’s swirling, swollen 1965 movie model of the Rodgers & Hammerstein musical has been a private favorite since lengthy earlier than I ever thought to record private favourites – a seasonal staple, a relentless generator of unprompted earworms, a degree of good-natured familial battle between those that like it and people who merely fake to not, a movie so laden with short-cut iconography that it rushes shortly to thoughts once I see a sure shade of upholstery, a selected bob haircut or perhaps a passing nun.

And but I’ve no reminiscence of the primary time I noticed it, the place I used to be or who hit play on the VCR, or when that unbeatable, unshakable music rating of cast-iron Broadway bangers first claimed a major chunk of actual property in my mind. I will need to have been so younger I didn’t precisely know what movies have been or how they labored; any older and people would all be vivid psychological milestones. Basically, for so long as I’ve been conscious of cinema, The Sound of Music has appeared to me its very essence – if not the perfect film ever made, the moviest film ever made, a Rosetta stone for the shape that everybody can learn and reference and recognise.

I may determine parodies of it earlier than I absolutely understood satire; its tunes would often floor and survive outdoors the context of the movie, whether or not on Christmas compilations – stray lyrical references to snowflakes and paper packages will do this for a music – or in nursery-school singalongs. Julie Andrews could have been the primary film star I understood as simply such an entity: with The Sound of Music and Mary Poppins each looming massive in my childhood canon, it appeared astonishing to me that her face and voice may someway be the driving pressure of each. Did all movies star Julie Andrews? I youthfully puzzled. It appeared to me they need to.

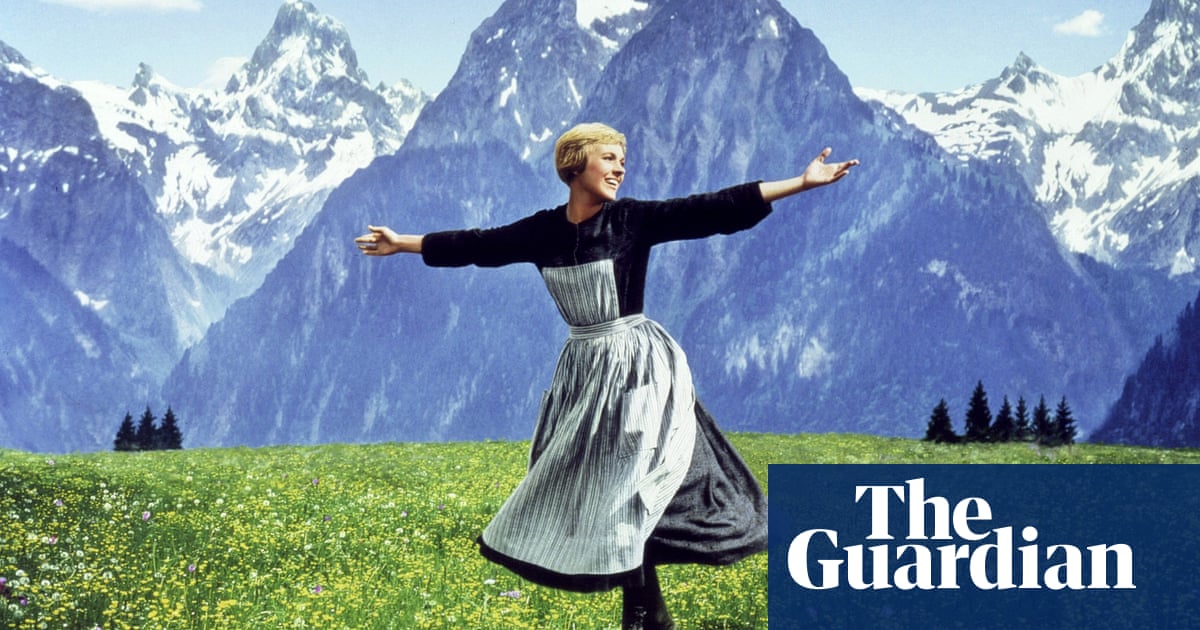

How a lot of the movie’s legend was based in its first two minutes? At a conservative estimate, I’d enterprise 90%. That absurdly grandiose opening shot was a history-making assertion of intent: that lofty, luxuriant lengthy view of the Bavarian Alps declares each a whopping price range and a sprawling departure from the confines of the Broadway stage, earlier than we drop and swoop into Andrews ecstatically swirling in an eye-searingly verdant meadow, as she launches into bell-clear music. To today I misremember if the digital camera is spinning greater than Andrews herself; the impact is so exhilarating that we really feel spun together with it. Who hasn’t, on encountering an open inexperienced area, felt not less than fleetingly compelled to unfold their arms and whirl freely, belting out out “thaaaa hills are aliiiiiive” on the high of their lungs? Many individuals, in all probability. But it surely feels to me a primal urge.

It’s a second of many kinds of magnificence fused into one: photographic, geographic, choreographic, excessive kitsch and excessive camp. I’d mistrust anybody who professes themselves unmoved by it in any manner and in reality, nothing in The Sound of Music fairly lives as much as that vertiginous opening salvo, for all of the tuneful, comforting, heart-plucking pleasures of the three hours that comply with. A lot of its inside drama is shot within the flat, beige home fashion of the period’s status studio cinema; past the perky, picturesque Salzburg location taking pictures of the Do-Re-Mi quantity, the movie’s prospers of scenic spectacle are sometimes a mere addendum to modest, simple, closely prolonged storytelling – a sprig of parsley on a beneficiant plate of meatloaf.

This imbalance solely turned clear to me on a hungover New Yr’s Day rewatch a few years in the past: I noticed The Sound of Music so many instances as a toddler that I took a close to 20-year break from the movie for it to regain its fascination, or me mine. After the infallible, head-clearing tonic of that first quantity, I used to be struck by the frequent smallness and occasional stiffness of the movie that after appeared to me as huge as any may very well be. The stilted love triangle between Andrews’ impossibly winsome Maria, Christopher Plummer’s improbably good-looking Captain von Trapp and Eleanor Parker’s unluckily jilted Baroness is the stuff of any dusty midcentury cleaning soap; the collective angst of the motherless von Trapp kids is vaguely written and blandly carried out. The movie urgently wants the stakes-raising intrusion of the Nazis in its second half; the breath-held rigidity of its climactic escape sequence could also be drafted in from one other film altogether, however essentially so.

And but The Sound of Music is, as ever, greater than the sum of its components. That features not simply the X-factor property of Andrews’ peachy luminescence and the miraculous alchemy that takes place between her and her grinning onscreen brood, or the irresistibly sticky high quality of even its worst songs – One thing Good, particularly, which I can nonetheless sing by coronary heart – however the unquantifiable private associations that every viewer brings to the movie. It’s, for me, a piece enriched by the numerous quote marks that encompass it now. That the already riotously chintzy Lonely Goatherd quantity is perpetually bonded in my thoughts with Gwen Stefani’s 2006 hip-hop makeover of the music solely intensifies the glee it brings me. That I can’t see Parker’s character with out mentally reciting the viral McSweeney’s letter formally saying the cancellation of her nuptials can also be the movie’s profit. As a movie, The Sound of Music has all the time been flawed; as a tradition objet, it will get ever extra diamantine.

It was later in my childhood, as my affection for the movie slotted right into a nascent cinephilia, that I discovered with some astonishment that it wasn’t universally thought to be a masterpiece – that Pauline Kael was fired from McCall’s journal for calling it a “sugar-coated lie” and “the sound of mucus”, and that many shared in her revulsion. Later, Slavoj Zizek would time period it a pro-fascist movie, to cheers from detractors who’ve lengthy felt pummelled by the musical’s deathless reputation. The Sound of Music was maybe the primary movie to alert me to the notion of essential subjectivity, to usually agreed strata of excellent style and dangerous style, and to the illicit thrills of having fun with the latter.

But it surely’s by no means turn out to be a responsible pleasure: there’s an excessive amount of earnest rapture within the movie for that, an excessive amount of trustworthy pleasure, an excessive amount of dizzily twirling pleasure. Movie anniversaries usually immediate reflections on the shortness of time, however on this case, I marvel that The Sound of Music is solely 60: it’s exhausting to consider that cinema lived and thrived so long as it did with out the movie’s most enduring photos, inspiring fantasy and mockery in equal measure, as elemental and immovable because the Alps themselves.

Supply hyperlink