It was a September evening in 2020 when the fireplace torched the Crimson Mountain Journey Plaza. Residents of the Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone nation watched as the one fuel station and grocery retailer for miles round vanished amid towering orange flames and acrid smoke.

The comfort retailer was the place the roughly 250 residents went to purchase snacks, tobacco and necessities. With out it, they must drive greater than an hour for main provisions. What’s extra, a protected stashed within the again room of the shop that tribal officers mentioned held practically $19,000 in money allegedly burned up. These have been a portion of the earnings from a hashish farm down the highway – 20 acres of land that have been the topic of a lot anger and nervousness on the reservation – and the tribe was relying on them.

One tribal official alleged that legislation enforcement from outdoors the tribe suspected arson, however nobody was charged. Many individuals in the neighborhood suspected that somebody had set fireplace to the fuel station so they might make off with the money. That was by no means proved. For many at Fort McDermitt, the harm was emblematic of one thing extra troubling: a mismanaged enterprise that by no means realized its promise.

“We have to get well what we misplaced right here,” mentioned Jerry Tom, an elder of the tribe, whose relentless seek for solutions got here to a head this yr. “Nothing good has come of the hashish enterprise.”

The Northern Paiute-Shoshone-Bannock folks from Fort McDermitt name themselves Atsakudokwa Tuviwa ga yu, or Folks of the Crimson Mountain. Their territory, which straddles Nevada and Oregon, lies amongst extensive expanses of sage brush, with the closest city, Winnemucca, 74 miles away.

Driving up Route 95 from Reno, an individual can go for hours with out seeing one other automobile. The highway passes a number of landmarks necessary to the tribe, together with a peak that served as a lookout when combating military cavalry within the 1860s. Bitterness nonetheless burns in regards to the exploitation of lands as soon as ruled by Indigenous folks.

Tucked away within the excessive desert, the reservation affords little in the best way of labor. The fortunate few have ranches, or work on the Say When On line casino down the highway, the tribal authorities or college. Many trek three hours to Boise, Idaho, or additional to work in mines.

Over the previous decade, public attitudes and state legal guidelines round hashish have relaxed, leading to a booming authorized weed market price an estimated $35bn nationally. In concept, the US’s 574 federally acknowledged tribes have a lot to achieve from it. In whole, they preserve about 56m acres of land in federal belief on which to develop, along with reservation lands. Being sovereign nations, they will largely use the land nonetheless they need, unimpeded by federal prohibitions on rising and promoting marijuana. For Fort McDermitt particularly, earnings from weed might translate into badly wanted jobs and cash for education and infrastructure.

However hashish is a dangerous enterprise. Dangerous climate can smash crops. It might take years to show a revenue. Because of the federal ban on weed, nationwide businesses don’t regulate Indigenous marijuana enterprises as they might casinos, leaving supervision to the Native nations, which regularly face restricted sources and restrictions on jurisdiction. (Fort McDermitt, as an illustration, doesn’t have its personal police pressure, so it should depend on the county sheriff and Bureau of Indian Affairs officers stationed an hour or extra away.) Tribes typically can’t get financial institution loans from large banks for the ventures and aren’t conversant in hashish cultivation, in order that they have to herald outdoors specialists and buyers. All of this and the cash-based nature of the enterprise could make Indian Nation weak to offers that go flawed.

That’s precisely what occurred when three white males from Oregon – Kevin Clock, Eli Parris and Darian Stanford – and their Native American collaborators sought to generate profits from Indigenous land. By the point they cleared out, seven years later, greater than a fuel station had gone up in smoke.

It was 2015, and the personal investor Kevin Clock was on the lookout for a win.

He and his pal Joe DeLaRosa had just lately visited Vancouver, Washington, to take a look at a preferred weed dispensary, and he’d had his eye on hashish ever since. “We realized it was a cash maker,” mentioned Clock, whose background was in “growth and land use and issues”, in an preliminary interview this spring. (He then declined to reply additional questions in regards to the operation.)

That acquired him desirous about Nevada, the place an initiative to legalize leisure weed was to be voted on the next yr, and particularly Native nations, the place he thought hashish retail shops and farms might discover success. Clock, a boisterous character with a knack for working a crowd, believed he might join with Indigenous communities as a result of he had attended highschool with Siletz folks in Oregon and had married a Native Hawaiian. “It’s the same tradition,” he mentioned.

To assist oversee future operations, Clock roped in Eli Parris, a quiet outdoorsman from Oregon with a background in actual property and finance who grew weed privately. To facilitate Indigenous outreach, Clock counted on DeLaRosa, the then tribal chair of the Burns Paiute of Oregon. DeLaRosa, who had beforehand labored because the monetary supervisor in a automobile dealership, couldn’t persuade his personal neighborhood to open a weed operation, however the staff thought he might persuade sister tribes to create a “Paiute pipeline”, whereby some nations would develop hashish and others would promote it.

In January 2016, the group contacted the leaders of the Fort McDermitt Tribal Council, which governs the reservation, to suggest growing a marijuana farm on tribal lands.

Clock and his associates promised to herald the required funding to get the operation off the bottom. They mentioned the farm could be 100% owned by the tribe and that the enterprise might create much-needed jobs and generate cash to enhance roads, housing, training and well being for years to come back. The mission might additionally function an anchor for different companies on this distant space.

Hearings have been known as on the reservation to current the proposal to the neighborhood. Vehicles crammed the parking zone and folks crowded into the constructing. A number of tribal members who have been current recalled guarantees that the farm would enrich the tribe. Some interpreted that to imply that they might every get a per capita share of the earnings, a method revenues from tribal casinos are distributed.

However some residents had issues about whether or not it was authorized to lease land to the hashish operation. Most of the older residents feared that introducing a marijuana enterprise would worsen substance abuse issues already plaguing the neighborhood. Others discovered Clock pushy.

“They got here in and painted a reasonably image and promised the tribe this and that,” mentioned Arlo Crutcher, an area rancher who attended the general public conferences (and who turned the tribal council chair just a few years later). “I mentioned, ‘This doesn’t sound too good.’”

He felt the boys dodged questions on operational issues and didn’t enable time for tribal officers to significantly contemplate the provide.

Crutcher thought others in the neighborhood have been too trusting of the boys’s pitch. He famous that his tribe lacked the enterprise savvy of richer nations with longstanding companies. Fort McDermitt had by no means had an enterprise of this scale. “The buyers knew they have been coping with gullible individuals, and so they took benefit of that.”

Nonetheless, representatives from Fort McDermitt reached an settlement with Clock’s staff in November 2016, closely pushed by Tildon Sensible, who quickly turned the tribal council chair. They established a 10-year partnership that may first pay Clock’s firm again any investments after which would give it 50% of income, an unusually giant reduce for businessmen not from the tribe. Like different tribal nations in Nevada, Fort McDermitt was to gather a hashish gross sales tax to fund important providers in the neighborhood. The outsiders would handle all of the financing and operations.

Quickly after, Clock introduced in Darian Stanford, a litigator who had labored as a deputy district legal professional prosecuting gang violence and main felonies in Oregon, to assist with authorized issues. Attorneys from a legislation agency the place Stanford ultimately labored have been retained at $400 an hour, and a five-member hashish fee was arrange by the tribal council and tasked with oversight of the operation to make sure issues remained above board. The fee was alleged to be accountable to the nation’s final authority: the tribal council. In an uncommon transfer, Parris, an outsider, in addition to two members from the tribal council, have been on the hashish fee, inserting them ready of supervising their very own efforts.

In response to Mary Jane Oatman, of the Nez Perce Tribe, who helms the Indigenous Hashish Trade Affiliation, that ought to have raised a crimson flag instantly. “There was no system of checks and balances,” mentioned Oatman, whose advocacy group guides tribes navigating the authorized weed realm. “They’ve members of the tribal council taking off their hats after which placing on the hat of the hashish fee. They need to have had an accountability system.” (Sensible and Stanford defended the observe, saying it allowed for the straightforward movement of data between the council and fee.) Stanford additionally turned the tribe’s choose a few years later, placing him on the heart of authorized disputes in the neighborhood; he recused himself from issues associated to the enterprise.

Round 2018, the newly created three way partnership – Quinn River Farms, named for the ribbon of water that flows by Fort McDermitt – was onerous at work, buying soil and farm tools, leveling land, putting in greenhouses and readying a constructing for storing and processing the harvests. Though Clock and his associates by no means turned fixtures in the neighborhood, Parris incessantly checked in on the location. They introduced in a foreman and employed dozens of tribal members who realized how one can domesticate crops, reduce buds and make pre-rolls. They have been typically paid in money, a typical business observe however one which makes it onerous to maintain observe of prices.

This was the imaginative and prescient: an emerald sea of towering marijuana crops that may change lives, with items offered to a different Paiute tribe and companies in Las Vegas, the place new weed lounges and dispensaries have been anticipated to open. Over the course of its operation, buyers would pour in thousands and thousands, within the hopes that it might be so profitable that it might set a normal throughout Nevada and for different tribes.

The outsiders moved shortly to understand that imaginative and prescient. The deal stipulated {that a} new LLC arrange by Clock and his companions would act as common supervisor and contract with consultants on behalf of Quinn River Farms, at all times in coordination with the tribe.

To that finish, Clock’s LLC introduced in Ranson Shepherd, a jiujitsu teacher initially from Hawaii who had been part of different profitable hashish enterprises. He took over administration and gross sales for the operation.

However Billy Bell, a member of the tribe’s hashish fee, mentioned in a memo that he later wrote to the tribe’s lawyer that he was involved about incomplete paperwork. (Bell declined to remark for this story.) He mentioned he had seen one model of the settlement with Shepherd the place the signatory line for the tribe, oddly, bore the identify of Parris, the one outsider on the fee.

The tribe was alleged to be an equal companion within the enterprise. Bell, nonetheless, felt it had been sidelined utterly.

Clock’s LLC and Shepherd “left the Tribe out of necessary and essential enterprise decision-making selections over the hashish mission”, Bell mentioned in his memo.

Tildon Sensible, the tribal chair and hashish fee member, was perturbed as effectively. Guarantees of further tools have been going unmet, he added.

“[Clock] promised us greenhouses inside so many months and that by no means occurred,” he mentioned. (Clock didn’t reply to request for remark about this and different allegations.)

In a memo after one of many first harvests, Sensible emailed Clock and Shepherd’s groups to share his frustrations that “everybody was doing their very own factor”, and that the tribe was being “ignored” and “now not thought of companions on this mission”.

Elders in the neighborhood additionally grew suspicious, Jerry Tom amongst them. After being away for years working in gold mines, Tom had just lately returned residence to Fort McDermitt, and he was disturbed to see that whereas the farm had began to develop hashish, he and different members of the tribe knew little about precisely how a lot cash the operation made or spent. He puzzled when, if ever, they might count on to see per capita funds from the enterprise.

“Nothing was disclosed to the tribal members,” Tom mentioned. “Nobody is aware of something about it.”

Crutcher, the rancher, concurred: “We had no clue how they have been working.”

Unease over the mission intensified when the 2019 harvest went poorly. The mission’s leaders blamed a tough freeze for hurting crops, and due to this fact gross sales. The tribe obtained about $100,000 from the 2018 harvest, and not less than $25,000 from 2019, however didn’t know if it was owed extra. Bell mentioned he feared the operation was producing extra money owed than income.

Tribal members puzzled in regards to the field vehicles that have been leaving the farm at evening and the place they have been going. Fort McDermitt residents noticed half a dozen transport out at a time.

All transactions have been carried out in money, as a result of issue of banking within the hashish business. Crutcher mentioned he had seen members of the hashish fee, buyers and tribal council members convey piles of cash to an administration constructing on the reservation to be counted.

Considerations in regards to the hashish operation price Sensible, the tribal chair, his re-election in November 2019. His successor was ultimately changed, this time by Crutcher.

Throughout this time, Clock referred tribal members’ many inquiries to Shepherd, who didn’t produce detailed monetary statements or invoices, in accordance with Bell’s memo.

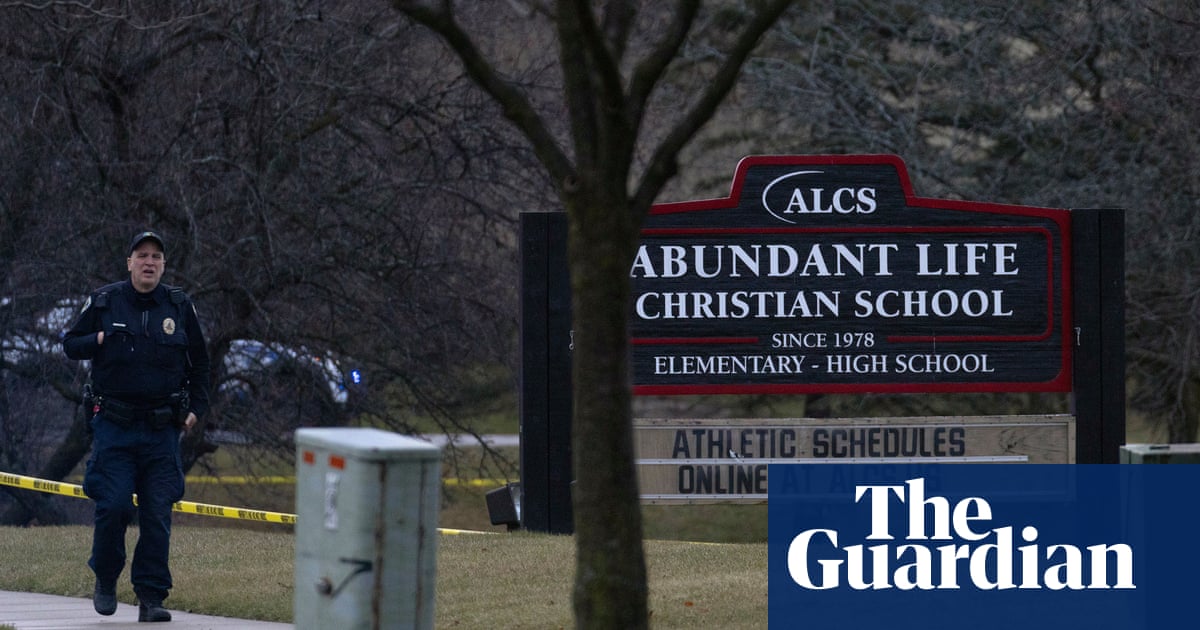

Then in September 2020, the journey plaza burned down with the alleged $19,000 in earnings inside. An inner investigation dealt with by Sensible, now a tribal administrator, by no means produced definitive solutions.

In an interview, Sensible mentioned he had moved the money from the tribal administration constructing to the fuel station earlier than the fireplace to maintain it out of the palms of incoming tribal council members. He denied accusations by some tribal members that he took the cash for himself and mentioned it had burned within the blaze.

With the journey plaza left in ruins, relations between the outsiders and the neighborhood went from unhealthy to worse.

In October 2021, trying to increase the enterprise, Clock and the staff introduced in additional buyers and signed a deal to domesticate extra acres. In response to paperwork shared with Bell, the present buyers had run up greater than $5m in bills, together with $63,258.85 in flights in addition to curiosity on loans from different firms, tools, salaries and transport. Underneath this newest settlement, the brand new buyers – a three way partnership involving Shepherd and an organization known as Hashish Life Sciences (CLS) – would pour one other $6m into Quinn River. Shepherd had additionally teamed up with CLS to supply pre-rolls projected to herald $600,000 in month-to-month income.

Tribal officers have been involved that these partnerships have been transferring too shortly, and that offers have been being negotiated with out their enter. Every new investor represented a success to the tribe’s general income share, steadily reducing what the tribe anticipated to earn.

Then jobs for native residents on the farm started to vanish, regardless that Clock’s group had instructed the tribal council that harvests had rebounded. The variety of Native workers dropped and employees from outdoors the reservation began appearing.

Even fewer hashish crops have been planted in 2022 than the yr earlier than, in accordance with Bell’s memo. When he visited the fields that summer season, just a few plots lay empty. The foreman later instructed him that the crops ultimately put within the floor may not flower on account of a late begin.

Gross sales sank and employees started dismantling tools and hauling it out. “They only packed up and left,” Crutcher mentioned.

The one public details about Quinn River’s funds, past what Bell and different tribal directors might collect, is in SEC filings by CLS. One exhibits a lack of greater than $100,000 from the enterprise for the yr ending 21 Could 2022. That was the final time Quinn River offered any hashish. CLS reported even better losses for the yr ending Could 2023 and pulled out of the deal, saying the enterprise Shepherd was concerned with had defaulted on its $3m contribution. The remaining employees have been laid off.

CLS declined a number of requests for remark. In an interview, Shepherd denied that he had defaulted, including that his enterprise didn’t owe $3m, as he had already invested within the needed infrastructure. “Why would you make investments into one thing that you simply already constructed?”

Fed up, the tribe enlisted its lawyer to contact Clock and Parris. “The Tribe wants detailed monetary reviews of the bills and earnings to the enterprise, not merely summaries,” the lawyer wrote. “The tribe must know when the bills incurred have been paid off in order that the earnings may be decided.”

Clock’s authentic group of buyers – himself, Parris, Stanford and DeLaRosa – weren’t capable of produce the requested paperwork. Parris mentioned they repeatedly – and unsuccessfully – requested Shepherd for gross sales information, financial institution statements and revenue and loss statements. “We by no means noticed any paperwork.” Shepherd disagreed, saying he had handed over all the required paperwork. “We supplied all documentation,” he mentioned.

Crutcher mentioned the lawyer suggested the nation to stroll away from the mission. “It’s costly to go after them. So we known as it quits.” (The lawyer declined to remark.)

Stanford confirmed that Clock’s group had agreed to terminate the contract and blamed Ranson Shepherd for the dearth of monetary reporting. “I 1,000% fault Ranson for not offering the monetary paperwork that have been requested,” he mentioned. “However I feel it’s sloppy, not malicious.”

The unique buyers’ fault lay “in not making certain that Ranson did no matter Ranson was alleged to do”, Stanford mentioned.

Within the last tally, the money Clock’s group handed to Fort McDermitt, from 2018 harvest revenues by to April 2022, totaled $564,450, in accordance with an announcement Bell supplied to the fee. Present and up to date tribal leaders don’t understand how this sum was calculated, what proportion of earnings it entails or whether or not they have been owed extra. Regardless of the sum, it was far lower than they anticipated to earn. Underneath Fort McDermitt legislation, 4% of the earnings from the hashish enterprise have been destined for per capita funds. Whereas the quantity per individual would have been minimal, Fort McDermitt residents mentioned they’ve obtained nothing in any respect.

Stanford mentioned the nation obtained quarterly funds and that his and Clock’s firm hadn’t made any cash. “When you ask me as we speak how a lot cash was made at McDermitt I do not know. I by no means noticed a penny.”

Parris concurred, saying any cash the outsiders have been entitled to was given to the tribe. The mission generated money to purchase a hearth truck and bury elders, he mentioned. “They may have made much more and they need to have made much more, however they made cash,” he mentioned. “We left the place higher in McDermitt than after we acquired there. I can 100% sleep on that for the remainder of my life.”

DeLaRosa characterised the mission as “profitable”. He mentioned that members of the group invested “hundreds of {dollars} of their private funds” to get the mission up and operating and by no means made “a single greenback”.

Shepherd additionally maintains that the tribe was correctly compensated regardless of his being within the crimson himself. He’s going through a lawsuit by an investor named Ting He, who alleged that he did not pay her again $3m, loaned in Could 2021. In response to the lawsuit, Shepherd mentioned the cash could be used to construct greenhouses and water wells and assist domesticate the hashish fields at Fort McDermitt. In return, she would additionally get a reduce of the harvest’s earnings.

The lawsuit alleges fraud and the misappropriation of funds, amongst different prices, and claims that Shepherd supplied He with a listing of bogus “bills” incurred by an organization he controls. A Nevada district court docket lists the swimsuit as lively, as He’s authorized staff has been unable to serve Shepherd with a summons and grievance, arguing that he was “now not responding” to calls or texts or answering the door – even with automobiles parked in his driveway. Nobody in Clock’s authentic group was named within the swimsuit. Requested for remark, Shepherd mentioned: “I can’t communicate on that till it’s full.”

Parris mentioned the group had totally vetted Shepherd forward of time. When requested if he and the others might have supplied oversight, he mentioned: “If anyone indicators as much as do one thing and so they simply don’t do it, what are you able to do outdoors of sue them, proper?”

Jerry Tom gained’t let the matter relaxation, not with so many unfastened ends. He served on the tribal council in 2019, and from then on collected no matter paperwork he might associated to Quinn River Farms – images, texts, Fb messages, movies, contracts, memos, minutes of conferences, authorized correspondence and extra. The foot-high file contains overlapping agreements, some with no signatures. Cashflow statements lack invoices or steadiness sheets to again them up. An merchandise itemizing leases for $17,000 doesn’t say who was leasing what. Two promissory notes of $600,000 have been written to firms some tribal officers have been unfamiliar with.

“We do not know if loans have been paid on time and even in any respect, or who accredited them,” Tom mentioned. With out correct invoices, the tribe lacks a transparent or full image of the mission’s funds.

Tom mentioned that the tribal council and the hashish fee did not adequately oversee the mission and share info with the neighborhood. Their conferences concerning the mission have been largely closed to the general public, and minutes have been unavailable.

Tom serves on the elders committee, entrusted with defending the cultural integrity of the tribe. In March 2024, he and different elders summoned the neighborhood to a gathering to debate the hashish debacle. Exterior the assembly corridor, a crimson painted signal declared: “KEEP YOUR ABORIGINAL RIGHTS!!”

About 50 folks filed in for a potluck supper earlier than getting all the way down to enterprise. The older girls chatted in Numu Yadooana, the Northern Paiute language, as they ate rabbit stew and beans. Tom served his signature pear and pumpkin pies.

The 5 members of the committee, seated at a protracted desk up entrance, known as the gathering to order.

“We didn’t see any paperwork, it was a hush-hush deal,” mentioned Larina Bell, the incoming tribal chair.

“They shared nothing with me,” mentioned Valerie Barr, the tribe’s finance director. “I requested for an audit. The tribe has been neglected, utterly.”

Speaker after speaker expressed anger, a sense of being tricked, preyed upon by the outsiders. “The place is the cash?” folks repeatedly requested. They wished to know why the tribe had made so little on the enterprise, and the standing of per capita funds.

The session continued for hours. Afterwards, as folks stacked chairs and cleared paper plates, Tom known as the assembly a “catharsis”. This was the primary time the neighborhood had come collectively to course of. “It was a trauma for our folks. We’ve got to unravel it.”

The controversies stored piling up. Unbeknown to the folks of Fort McDermitt, Clock’s group was working with 4 different Nevada tribes on hashish ventures by a constellation of LLCs across the identical time Quinn River took in its first harvest. Tribal representatives and Indigenous leaders who did enterprise with them described the boys’s course of as cultivating a relationship with somebody distinguished within the tribe and holding different officers at arm’s size. Between 2019 and 2023, practically all of those ventures confronted pushback.

The Las Vegas Paiute left the partnership, in accordance with the tribe’s common counsel. The partnership’s dissolution was hashed out privately, in accordance with business sources. The Pyramid Lake Paiute shut down their develop in 2019 after only a few months and pursued the outsiders in tribal court docket, in accordance with minutes of the tribal council. A building contractor filed a $2.3m mechanics lien towards Clock’s group for alleged non-payment.

Controversy nonetheless swirls across the Newe dispensary, opened in 2020 with the Elko, one of many 4 bands of the Te-Moak of the Western Shoshone. A former tribal chair of Elko, Felix Ike, complained of an absence of transparency across the determination to open the dispensary and an absence of correct legislation enforcement, in accordance with reporting within the Elko Every day. He and others tried, unsuccessfully, to get it shut down.

Clock denied there had been points with these tribes. He mentioned that the enterprise mannequin was to go in, get a mission up and operating after which hand over administration to the tribe. That by no means occurred at Fort McDermitt.

As for Pyramid Lake, Stanford known as the nation’s determination to close down the develop “horrible” and dear.

He blamed lots of the setbacks, together with at Fort McDermitt, on modifications in tribal management. “The most important problem on this total business is turnaround in tribal management,” he mentioned. “There’s no institutional reminiscence typically.”

DeLaRosa, the tribal liaison for the buyers, mentioned Fort McDermitt’s “desolate” location made it onerous to draw contractors and created different challenges. He added that divisions inside Native nations might complicate doing enterprise. “Typically it’s simply the dynamics of the neighborhood.”

Nonetheless, Clock, Parris and Stanford stored transferring. In 2021 they submitted a proposal to work with the Jap Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina – a relatively rich nation that owns a profitable on line casino, Harrah’s, within the Nice Smoky Mountains.

This operation acquired off the bottom: a glitzy 10,000 sq ft dispensary, state-of-the-art processing tools and a 22-acre develop. The tribe financed the three way partnership with greater than $30m of its personal cash, moderately than relying solely on exterior buyers as Fort McDermitt had carried out.

On the launch, Clock and the others appeared to be operating the present. Clock darted about, slapping folks on the again, whereas Stanford directed folks on the place to face for picture ops. Parris and DeLaRosa additionally attended the occasion, largely holding to the sidelines.

Morale appeared excessive among the many 100 workers. However this mission, too, confronted issues about transparency. The earlier yr, the then principal chief, Richard Sneed, vetoed allocating a further $64m till the three way partnership accounted for the $30m invested by the tribe up to now. He apprehensive about potential price overruns, and the potential use of on line casino revenues, which might endanger federal grants. He wished to see a correct audit.

Sneed mentioned in an interview that he hadn’t been capable of get solutions from the enterprise’s board or the tribal member they employed as the overall supervisor. “I requested some fundamental questions. Do you’ve gotten agendas in your conferences? No. Are you holding minutes? No.”

He mentioned they’d additionally failed to offer him a fiscal administration coverage and quarterly reviews.

Stanford, nonetheless, mentioned an unbiased audit had confirmed the whole lot was “100% kosher”. The enterprise’s common supervisor confirmed the audit had been carried out.

Sneed misplaced his re-election in September 2023, and the mission moved forward with a portion of the $64m the tribe had deliberate to speculate.

Extra tribes could quickly face a alternative about entering into the weed enterprise, after the US justice division proposed regulatory modifications to permit using hashish for medicinal, though not leisure, functions below federal legislation.

Nevertheless, the troubles at Fort McDermitt and elsewhere concern Oatman, of the Indigenous Hashish Trade Affiliation.

“The larger systemic problem for tribal communities is that the whole lot is so covert and underground, with out the insurance coverage and banking that enable entrepreneurs to do due diligence,” she mentioned. “Discovering a trusted companion turns into a chicken-and-egg downside as a result of it’s a brand new business. Many tribes lack the sources for the foundational work that must be carried out by way of licensing.”

She encourages tribes to train excessive warning when vetting companions and contractors, and to not promise away large consulting charges and fairness shares.

Not less than one tribe has steered clear after listening to what Fort McDermitt and different tribes went by. Bobbi Shongutsie of the Wind River Reservation is wanting into opening a hashish operation on behalf of her tribe in Wyoming. She toured the dispensary at Elko, arrange by Clock. She didn’t just like the “minimal” safety nor that different tribal ventures involving the group had shut down. “That was a crimson flag,” she mentioned. Her tribe determined to go on doing enterprise with them.

A separate group of tribes in Nevada took one other path completely and arrange their very own self-regulated business that doesn’t depend on outsiders. Oatman mentioned this community, which incorporates Shoshone and Paiute nations, might function a mannequin.

Again at Fort McDermitt, the journey plaza nonetheless hasn’t been rebuilt. Cables jut out of the cement between ruined petrol pumps, like metallic cobras. The hashish fields down the highway lie fallow. Torn tarps from greenhouses flap within the wind.

Round Christmas 2023, thieves broke into the constructing that had served because the hashish processing facility and made off with unsold merchandise, which tribal officers believed weren’t match for consumption. Surveillance cameras didn’t work due to unpaid electrical energy payments. After the housebreaking, minors as younger as fifth grade have been seen with hashish on college property. Tribal officers imagine the medication had come from the work website.

A couple of month after the theft, officers burned 525lb of hashish buds and trim and practically 5,000 pre-rolls and boarded up the constructing.

Throughout a go to in March, Tom milled about with different elders and former workers who had misplaced their jobs when the operation shut down. Tom suffers from an outdated leg damage, and he limped slowly with a brace among the many decayed plots. Crutcher, by then the outgoing tribal chair, joined, too. He contemplated what to do with an deserted storage shed, trailer and the skeletons of the greenhouses.

“They promised we’d generate profits, after which, nothing,” mentioned Janice Sam, who used to work on the develop.

Her former co-worker, Wacey Dick, was extra direct: “They lied to us.”

The group walked to the storage shed. It held about 20 plastic containers stacked 9ft excessive and stuffed with leftover product that hadn’t been torched, not less than not but. Free piles spilled on the ground, rotting within the moisture.

Crutcher kicked the warped door. “We’ve acquired to place a plan collectively, in any other case we’re going to proceed to have folks coming in and pulling wool over our eyes once more.”

As the tip of the yr drew shut, tribal officers mentioned the time for hashish cultivation had handed. One other group of outsiders had introduced a proposal to revive the farm a number of months earlier. The tribe refused to listen to them out.

This story was funded partially by a grant from the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

-

Judith Matloff is on the school of Columbia College’s Graduate College of Journalism. Her work has appeared in main media, together with the New York Instances, the Wall Avenue Journal, the Guardian and the Los Angeles Instances

Supply hyperlink