Standing earlier than the Royal Society of Medication in London on 22 June 1972, the ecologist turned psychologist John Bumpass Calhoun, the director of the Laboratory of Mind Evolution and Conduct on the Nationwide Institute of Psychological Well being (NIMH) headquartered in Bethesda, Maryland, appeared a mild-mannered, smallish man, sporting a greying goatee. After what should certainly have been one of many oddest opening remarks to the Royal Society in its storied 200-plus-year historical past – “I shall largely communicate of mice,” Calhoun started, “however my ideas are on man, on therapeutic, on life and its evolution” – he spoke of a long-term experiment he was operating on the results of overcrowding and inhabitants crashes in mice.

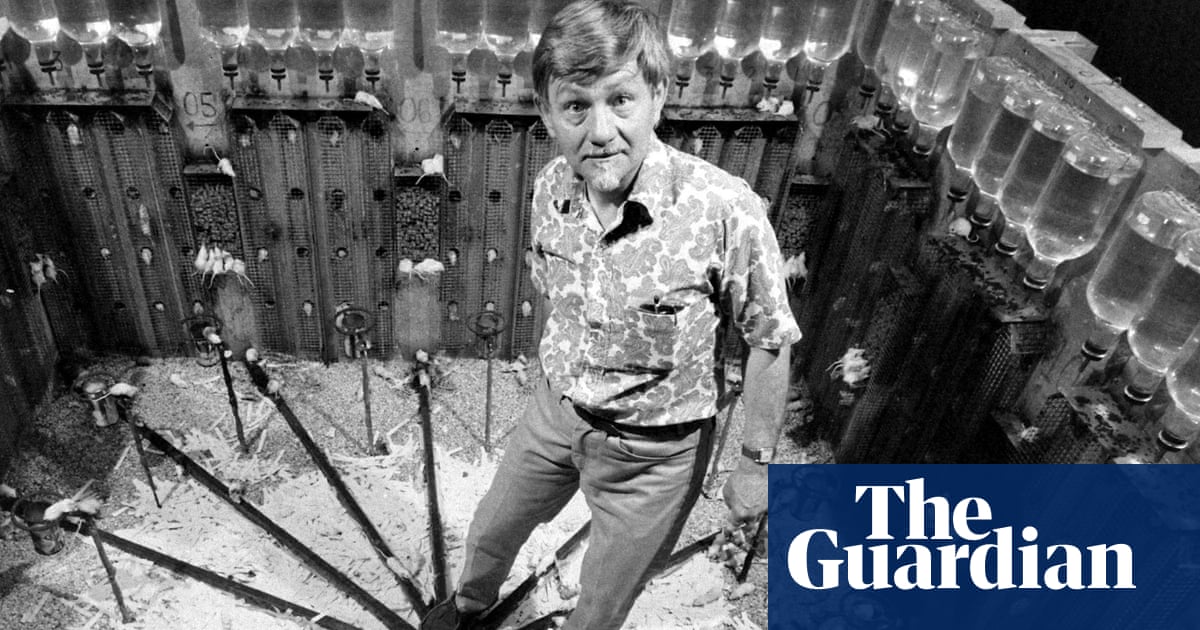

Members of the Royal Society have been scratching their heads as Calhoun instructed them of Universe 25, a large experimental setup he had constructed and which he described as “a utopian surroundings constructed for mice”. Nonetheless, they listened rigorously as he described that universe. They realized that to check the results of overpopulation, Calhoun, along with being a scientist, wanted to be a rodent metropolis planner. For Universe 25, he had constructed a big, very intricate condo block for mice. There have been 16 similar condo buildings organized in a sq. with 4 buildings on all sides. Calhoun instructed his viewers every constructing had “4 four-unit walk-up one-room residences”, for a complete of 256 items, every of which might comfortably accommodate about 15 mouse residents. There have been additionally a sequence of eating halls in every condo constructing, and a cluster of rooftop fountains so the residents might quench their thirst. Calhoun had marked every mouse resident with a singular color mixture and he or his crew sat in a loft over this mouseopolis, for hours daily, for greater than three years, and watched what unfolded.

Calhoun instructed the Royal Society members that what started as a rodent utopia – the place mice had luxurious lodging, all of the meals and water they might need, and have been free from the dual scourges of illness and predation – over time degenerated right into a mouse hell. Initiated by a inhabitants explosion early on, and later stagnation and decline, that hell had mice displaying a collection of aberrant behaviours, together with the lack of sexual drive on the a part of males and the absence of maternal care in females. Calhoun attributed a lot of this to the formation of what he referred to as a behavioural sink that had developed among the many mice in Universe 25. On the most basic degree, a “behavioural sink”, Calhoun argued, was an “attraction to at least one locality to guarantee a conditioned social contact”. That attraction might result in a “pathological togetherness” wherein animals wanted to be close to others, even when the implications of such togetherness – consuming at crowded feeders when extra meals could possibly be obtained elsewhere – have been unfavourable. As soon as a behavioural sink was in place, “regular social organisation … ‘The institution,’” he instructed the group, “breaks down, it ‘dies.’”

Even when mice have been taken from Universe 25 and positioned into one other mouse condo block with a a lot decrease density of residents, Calhoun defined, they nonetheless confirmed these aberrant behaviours. As he summarised his outcomes, Calhoun once more befuddled his viewers, telling them of a category of mice that had appeared after the rodent inhabitants bomb had exploded and the inhabitants had rocketed. These have been what Calhoun dubbed “the Lovely Ones” – mice that spent their time grooming themselves and consuming and shunned all social behaviour. The Lovely Ones, Calhoun instructed his viewers, have been “succesful solely of the simplest behaviours appropriate with physiological survival”. In time, Calhoun got here to imagine that if we didn’t act to cease a possible human inhabitants bomb from igniting, we’d see human parallels.

Calhoun’s work a decade earlier, that point on rats in a barn he had was a laboratory, had already been the topic of a lot consideration, garnering tales in newspapers world wide – however now, at the side of the mice in Universe 25, his research of crowding, inhabitants development and the perils of overpopulation in rodents took him to worldwide consideration.

No one in attendance at Calhoun’s lecture on the Royal Society of Medication would quickly overlook what they heard. A few of the society members knew of Calhoun’s article in Scientific American a decade earlier. That article, on crowding and inhabitants crashes in rats, opened with allusions to the 18th-century political economist Thomas Malthus and his concepts on overpopulation and distress. Calhoun then adopted with an outline of his personal leads to rats, which centred on the results of overcrowding and unconstrained inhabitants development. However the Universe 25 mouse experiment outcomes have been totally different. And never simply due to the Lovely Ones, or as a result of these outcomes confirmed what Calhoun discovered within the rats a decade earlier, however as a result of the work was a lot grander, with hundreds of mice and a few years of information on a subject – inhabitants development and decay – that was of nice concern, and never simply to scientists. A big swath of the general public on the time was scared of the implications of human inhabitants development as nicely – largely due to Paul R Ehrlich’s 1968 ebook The Inhabitants Bomb, which shot to the bestseller record after Ehrlich appeared on The Tonight Present with Johnny Carson.

Calhoun’s work was lined within the New York Instances, the Washington Publish, Time journal, Der Spiegel and extra: “It was a stunning day,” learn the opening sentence of a 1970 Newsweek story, “a lot too beautiful to spend in an workplace. In actual fact, it appeared the proper day to go to Dr John Calhoun’s mousery.” In Time journal’s 1971 article, Inhabitants Explosion: Is Man Actually Doomed? the author notes grimly that “even when a way might be discovered to feed the onrushing tens of millions [of humans], they could nonetheless face a psychic destiny much like the one which befell Dr John Calhoun’s white mice”. In April of that 12 months, the US Senate mentioned Calhoun’s works on overpopulation in rodents and the implications for our personal species, and it enshrined three of his papers within the congressional file.

Many noticed Calhoun’s work on overcrowding and inhabitants dynamics as a portent of doomsday, however he thought in any other case. Calhoun got here to see the outcomes of his work with rodents as prescriptive, exhibiting a path ahead to stop the human inhabitants bomb from exploding. Many agreed, however he had his critics, then and now. He dubbed himself a “℞evolutionist” – a revolutionary evolutionist with a prescription (℞) to assist struggle the issues of overpopulation. He referred to as his concepts “metascientific,” which, for Calhoun, meant utilizing science to attempt to perceive very complicated issues involving not simply many unknowns however complicated interactions between variables. To drive residence that complexity, he proposed experiments in rats that may tinker with rodent tradition and cooperation, and in so doing, defuse a possible ticking inhabitants bomb. “After all, we realise that rats aren’t males,” Calhoun as soon as mentioned, “however they do have outstanding similarities in physiology and social relations. We will no less than hope to develop concepts that may present a spring ahead for attaining insights into human social relations and the resultant state of psychological well being.”

Each version of Forty Research That Modified Psychology, from the primary in 1992 to the most recent in 2020, has a chapter that reprints Calhoun’s 1962 Scientific American paper. However, in some ways, essentially the most profound influence of Calhoun’s research lies removed from tutorial halls and ivory towers. By the seemingly limitless protection in newspapers and magazines, Calhoun’s work seeped into the general public consciousness. Metropolis planners and designers within the Seventies and Eighties regarded to Calhoun’s outcomes when designing housing developments, and he inspired them to take action. Annually, Ian McHarg, who years later was awarded the Nationwide Medal of Arts and the Thomas Jefferson Basis medal in structure, introduced Calhoun to lecture on the interdisciplinary programme of panorama structure on the College of Pennsylvania. Calhoun hadn’t all the time talked of mice whereas pondering of males, however by the mid-Seventies, outcomes from his research over the earlier 25 years led him to imagine he had an ethical accountability to take action.

Movie producers and writers of fiction and nonfiction clamped on to Calhoun’s concepts and included them into their very own work. Web page after web page of Tom Wolfe’s 1968 ebook The Pump Home Gang – revealed on the identical day as his The Electrical Kool-Help Acid Take a look at – paid homage to Calhoun’s concept of a behavioural sink. Calhoun’s work, partly, led one of many writers of Catwoman to introduce the character Ratcatcher to the caricature. The bestselling youngsters’s ebook Mrs Frisby and the Rats of NIMH could have had its origin in Calhoun’s rat experiments. On the very least, Calhoun thought it did, based mostly on a go to by the writer, Robert Conly (who wrote beneath the pseudonym Robert C O’Brien), to his lab at NIMH. And the record goes on and on.

In maybe the oddest twist of all, as early because the Sixties, Calhoun’s research of mice and rats led him to dedicate a great deal of the later years of his profession to engaged on the creation of a human “world mind”. “We at the moment are on the vital transition to a brand new kind of man,” Calhoun instructed an viewers in 1969, “one which relies upon more and more on extracortical prostheses to evolve and utilise ideas.” Calhoun was satisfied that by linking collectively these extracortical prostheses – akin to right now’s web hubs – we would be capable of harness creativity and, amongst different issues, determine a manner out of the overpopulation drawback. By no means one to shrink back from daring prediction, Calhoun instructed this similar viewers that “a tough calculation signifies that by 40,000 years from now lower than 5% of artistic exercise will probably be accomplished by our cortex and no less than 95% by prostheses”.

When Calhoun died of a coronary heart assault and stroke he suffered whereas on vacation in 1995, the New York Instances and Washington Publish ran obituaries. Each described the behavioural sink (although they didn’t use the time period), in addition to rodent universes filled with Lovely Ones.

A 2017 Washington Publish article described Calhoun as a person “who achieved the popularity attained by solely a handful of different social scientists, comparable to Pavlov and Skinner”. Definitely, within the 60s and early 70s, Calhoun’s work generated large consideration. However the lasting influence of his work is nowhere close to that of Pavlov’s work or Skinner’s work, which have formed and proceed to form analysis programmes world wide and are mentioned, at size, in practically each psychology textbook, in addition to many an animal-behaviour textbook (together with my very own). Certainly, within the grand scheme of issues, Calhoun’s work has not fared nicely on this planet of academia.

It’s true that, in its heyday, Calhoun’s work on rats and mice is also present in animal-behaviour and psychology textbooks. However a assessment of textbooks in these fields right now exhibits nearly no point out of Calhoun’s research. And to discover a dialogue of Calhoun’s work in tutorial journals right now isn’t any simple matter both. Whereas the historians Jon Adams and Edmund Ramsden have written a sequence of fantastic papers that have a look at Calhoun’s work, these papers are revealed in journals comparable to Comparative Research in Society and Historical past and Journal of Social Historical past – journals that researchers learning evolution, animal behaviour, inhabitants dynamics and psychology would hardly ever, if ever, learn. Occasionally, a PhD dissertation will nonetheless cite a number of of Calhoun’s research, however these are typically citations to point out that the writer has accomplished their historical past homework somewhat than citations suggesting that Calhoun’s work helped form the concepts within the dissertation. Net of Science, the main quotation index for scientific papers, exhibits that just about none of Calhoun’s papers are cited any extra. The one exception is his 1973 paper Demise Squared: The Explosive Development and Demise of a Mouse Inhabitants, revealed within the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medication, which remains to be cited now and again, though nearly by no means in a significant animal behaviour or psychology journal.

Why has Calhoun’s work not fared nicely on this planet of academia? For one factor, after he revealed his Demise Squared research, Calhoun hardly ever revealed his leads to mainstream science journals, and, certainly, lots of his research, together with these on Universes 33 and 34 – wherein he examined whether or not cooperation lowered explosive charges of inhabitants development in his rodents (it did) – have been by no means revealed in any respect. Phrase of these research would solely have unfold by individuals who heard Calhoun lecture about them or learn a point out of them in a assessment paper Calhoun wrote in his later years.

Calhoun’s typically glib use of anthropomorphic terminology has additionally damage his standing on this planet of science. As we speak, the type of anthropomorphic language – “Lovely Ones”, “common autism”, “pied pipers”, “somnambulists”, and extra – that Calhoun used to explain rodents, even in his most technical papers, is not only frowned upon however considered unprofessional, in addition to harmful. It’s troublesome to think about an editor of a significant journal in animal behaviour, evolution or psychology permitting an writer to explain extraordinarily aggressive people as “berserk”, as Calhoun did. Anthropomorphism was frowned on on the time Calhoun was doing his experiments as nicely, however there was rather more leeway. In an analogous vein, whereas most scientists right now and in Calhoun’s day would agree that behavioural and evolutionary work in nonhumans can inform our understanding of ourselves, the concept that a handful of research in a small variety of species might or ought to influence coverage selections is approached with a lot better trepidation. However, in his papers and in his lectures, Calhoun would typically slip into language that, on the very least, made it seem as if his coverage suggestions did certainly stem largely from his work on two species of rodents.

Within the area of animal behaviour, and to a lesser extent in psychology, one more reason Calhoun’s work has fallen off the map is that there was a major shift in perspective towards detailed cost-benefit analyses within the research of nonhuman behaviour. Calhoun thought of the prices and advantages of social behaviour in his universes, however he wasn’t all that involved with straight measuring these prices and advantages or casting his work in an express, cost-benefit framework. For instance, versus the method Calhoun took to the preventing that occurred in his rodent universes, a research of aggression right now may measure the dimensions of the combatants, the quantity of vitality expended on various kinds of preventing behaviour, the danger related to totally different ranges of preventing, the advantages linked to successful a struggle, and extra. Work on inhabitants dynamics and behavior has additionally modified radically since Calhoun undertook his experiments.

Some scientists retain vivid recollections of Calhoun, his work, and its long-term influence (or lack thereof). When Stephen Suomi, who moved into Calhoun’s area at NIMH, appears to be like again on the physique of Calhoun’s work, he’s most impressed by one factor: “He anticipated,” Suomi says, “the cross-disciplinary integration mandatory to actually research complicated developmental issues.” Highly effective reward, certainly, for Calhoun the thinker. Neil Greenberg, an animal behaviourist who, as a postdoc, overlapped briefly with Calhoun at NIMH within the Seventies, casts Calhoun’s work because the type of materials that will get undergraduate college students excited in regards to the research of behaviour. “I ended up utilizing a few of his analysis as gee-whiz form of stuff for educating,” he says right now.

Maybe greater than the rest, the explanation references to Calhoun’s work on his rodent universes have plummeted within the scientific literature is as a result of no proof for the behavioural sinks, Lovely Ones, or different observations that Calhoun detailed in his rat and mouse universes has been present in wild populations of animals – rat, mouse, or in any other case. A part of that’s, little doubt, as a result of for the previous few many years, nobody has been explicitly searching for these items when working within the area. However within the 70s and early 80s, most animal behaviourists in biology and psychology departments would have been aware of Calhoun’s work, but area research then (and later) on inhabitants dynamics weren’t discovering something that resembled Calhoun’s conclusions.

In contrast to its destiny within the academy and its technical journals, thanks not solely to Catwoman, The Pump Home Gang, Mrs Frisby and the Rats of NIMH and the a whole lot of newspaper articles that got here out his work throughout his lifetime, but additionally to modern common science articles, podcasts, and extra, Calhoun’s work lives on in our collective consciousness and has remained a topic of fascination in common tradition. In spite of everything, how might the general public not be endlessly fascinated with the US Senate discussing rodent utopias turned dystopias filled with “Lovely Ones” scampering about rodent condo complexes? Or “pied piper” mice following round a researcher who instructed a set of the perfect scientists on this planet that his work could “sound like rantings of a mad egghead locked up in his ivory tower”, and who needed to put in writing a ebook referred to as The Rodent Key to Human Survival?

This essay is tailored from Dr Calhoun’s Mousery: The Unusual Story of a Celebrated Scientist, a Rodent Dystopia and the Way forward for Humanity revealed by The College of Chicago Press.

Supply hyperlink