Tim Hetherington used to get so hung up about time. This was his difficulty on each images task, his primary bone of rivalry: how a lot time did he have? He may by no means perceive why a author was allowed a full hour with a topic whereas the photographer needed to shoot across the edges, grabbing 10 minutes right here and there. “Maintain on, maintain on,” he would say, each time I dared hurry him. He had vital work to be doing. He completely refused to be rushed.

Tim and I have been colleagues again within the late Nineteen Nineties after we have been each on the Huge Situation journal. The editorial workplace was like a dysfunctional household: everybody combating their nook and principally studying on the job. For a few of us, it was house, however Tim was solely passing by way of, sure for wilder locations and larger glories. He joined insurgent convoys in west Africa, bunked alongside GIs in Afghanistan and chronicled the primary inexperienced shoots of the Arab Spring. He received a quartet of World Press Photograph awards and earned an Oscar nomination for Restrepo, the struggle documentary he made with US creator Sebastian Junger, drawing on their 15 months embedded in Afghanistan’s Korengal Valley. On task, his strategy was methodical and deliberate. In life, he went at issues full-speed. It was as if he was working to his personal inside stopwatch, subconsciously conscious that he needed to benefit from every second.

Now alongside comes Storyteller to place an additional twist within the timeline by stitching Hetherington into historical past. This bumper exhibition, on the Imperial Battle Museum in London, options his pictures and movies, his journals and cameras. Tim’s photos inform us vivid tales about women and men on the frontline. However not directly, implicitly, they inform us his story as effectively. The retrospective leads the customer remorselessly, step-by-step, from his early work in Liberia, by way of to Sierra Leone and Afghanistan, all the best way as much as his closing days in Misrata, overlaying the Libyan civil struggle.

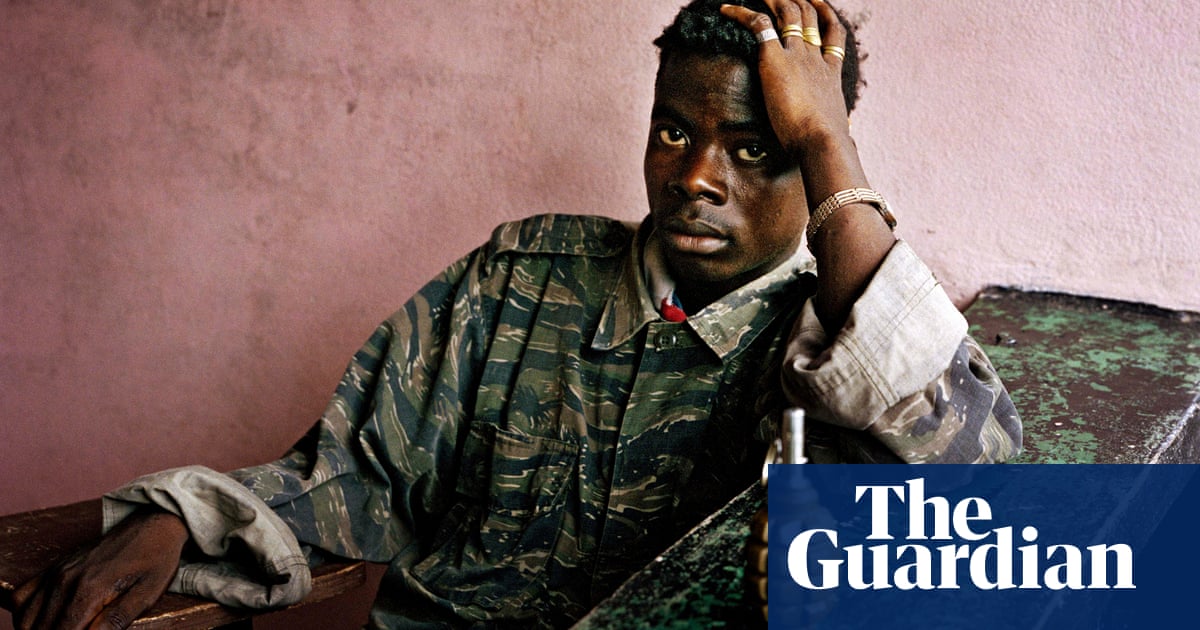

The stereotype of the struggle photographer is of a thrill-seeker, a free cannon, babbling on the sidelines like a demented Dennis Hopper in Apocalypse Now. However Tim wasn’t like that. He was severe and idealistic, diligent and principled. He got here to battle by way of humanitarian work and this exhibits in his photos, that are extra all in favour of army software program than {hardware}, fascinated by the human cogs within the machine and the relationships between them. So he’s drawn to what may in any other case be dismissed as small particulars: the knackered younger insurgent together with his hand grenade on the counter; the bullet-headed captain who cradles a small canine he’s adopted; the bored troopers wrestling on the ground of the barracks. The photographs in Storyteller are nuanced and empathic. Again and again, they discover unconventional routes by way of the carnage.

“That’s why so many photographers have been influenced by him,” says present curator Greg Brockett. “When you discuss to individuals within the trade, all of them know his work and assume it’s nice. Once you discuss to most people, they’ve by no means heard of him. So hopefully this introduces him to a wider viewers, as a communicator, an interpreter – somebody who appears at battle in visually impactful methods however who talks about it in methods they by no means would have anticipated.”

Usually, tellingly, Tim labored at his personal tempo. At a time (the early 00s) when most photojournalists have been crossing to digital, he shot color destructive movie on an analogue digicam: 10 frames on every roll. This compelled him to consider carefully about every composition, lifted him out of the frantic information cycle and nudged him in the direction of such long-term themed initiatives as his sensual Sleeping Troopers collection, , with its elegant framing of servicemen at relaxation. Tim favored circling again to revisit individuals and areas. Better of all, he favored immersing himself inside a gaggle dynamic. Embedded alongside Junger within the mountains of japanese Afghanistan, the pair condensed a whole bunch of hours of footage to make Restrepo, named after the platoon medic who was killed early within the tour.

At the moment Tim has been typecast. The frontline is his legacy. The photographer Stephen Mayes, govt director of the Tim Hetherington Belief, has blended emotions about that. “Tim has now reached the purpose the place he’s turned from reminiscence to historical past,” Mayes says. “Historical past will selectively view us because it needs and there’s nothing we are able to do about that. However I believe he’d be appalled to be represented as a struggle photographer. That’s not how he outlined himself. The human traits he was all in favour of revealed themselves most strongly in instances of battle. However his topic wasn’t struggle. It was extra profound: it was individuals.”

I communicate to James Brabazon, the frontline journalist who labored with Tim in Liberia. Brabazon recollects their experiences in 2003, overlaying the Lurd insurgent advance on the capital, Monrovia. Bullets flying. Casualties left and proper. He says that 80% of struggle reporting is logistics. It’s about staying hydrated, protecting protected, shifting between areas, resting when you possibly can. The danger, in spite of everything that, is that you just’re too exhausted to concentrate to the story. To give attention to the human beings. To recollect why you’re even there.

“To be sincere,” he says, “I’ve discovered it a drag, having to be all in favour of different individuals. I wish to say, ‘Please, simply let me be alone in my hell.’ However Tim was all the time super-engaged. His curiosity and humanity persevered by way of all of it – nonetheless intense it had been, nonetheless traumatised he was. And so they deeply affected him, the occasions that he witnessed. He carried deep psychological hurt for the remainder of his life. However one way or the other, he may then flip round and create magnificence out of horror. He may instantly sit down with somebody and seize the essence of humanity that one way or the other existed exterior the structure of struggle.”

On 20 April 2011, Tim was filming contained in the besieged metropolis of Misrata when the insurgent military was shelled by Gaddafi’s authorities forces. His femoral artery was lower by a small piece of shrapnel. He bled out within the van, a couple of minutes from hospital.

“It’s troublesome,” says Brabazon. “I’ve spent years making an attempt not to consider it. I want I’d been there. I want I’d been with him. Sebastian feels the identical. We each function underneath the robust delusion – or certainty, relying on our temper – that Tim would nonetheless be alive if we have been with him that day.”

Tim’s loss of life nonetheless feels unusual. It leaves the person mounted in time, endlessly 40 years previous, as a lot a bit of historical past lately as his Arab Spring photos. It additionally prompts others to talk on his behalf. The unfinished Libya work is flash-lit, hyperreal and incorporates a component of efficiency. Tim had began taking photos of photographers taking photos. He appeared fascinated by the suggestions loop of warfare, the best way through which one picture of battle influences one other. Brockett thinks that this may increasingly have been his subsequent course: a challenge centered on the theatre of struggle. Finally, there isn’t a method of realizing.

Tim’s closest associates prefer to joke that their two most dreaded phrases are “Tim would”. Tim would have thought this, Tim would have finished that. The purpose is that it’s ridiculous, says Mayes, as a result of no person has a clue. “Even Tim didn’t know. Tim didn’t totally know who he was. He didn’t know the place he was going. I knew him for 15 years and he was all in regards to the journey.”

By 2011, thinks Mayes, Tim had largely fulfilled his agenda. “He’d explored the world. He’d explored multimedia. He had recognition, an viewers, an Oscar nomination. The tragedy was that he was lower off with a full cease on the finish of a sentence. He was about to start out the subsequent sentence. No one is aware of what it will have been.”

Simply earlier than his loss of life, Tim produced a 19-minute documentary referred to as Diary. It’s a effective piece of labor: a freeform, summary audit of 10 years of struggle reporting, cross-cutting between rainwashed African roads and bustling London streets, dropping us with out preamble into the aftermath of a bloodbath in japanese Chad. Tim has come to report the stays: the damaged pots, the burnt corn-cobs and the charred human-shaped shadow laid out on the grass.

“Maintain on, simply maintain on,” he tells the African information who tries to maneuver him alongside – and there it’s, like a seance, our photographer from the previous. Daring and sensible, authoritative and exasperating. He was continually demanding extra time, the awkward bastard. There have been all the time so many issues that he wished to do.

Supply hyperlink