In response to nationwide pollsters’ failure in forecasting election outcomes in 1948 and 1952, The New York Instances pursued in 1956 a weekslong, multistate train in on-the-ground reporting to evaluate public opinion concerning the presidential race.

The Instances’ experiment, which today can be acknowledged as “shoe-leather reporting,” included two dozen journalists assigned to 4 groups that, in all, traveled to 27 battleground states over a number of weeks earlier than the election – a rematch between President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican, and his Democratic rival, Adlai E. Stevenson.

The reporting groups interviewed scores of People from all walks of life in an try to gauge voter preferences qualitatively – with out counting on the info of preelection polls. One of many collaborating Instances reporters declared afterward that the teams-based marketing campaign protection represented “a brand new departure in journalism.”

In unintended testimony to the challenges of measuring public opinion throughout a sprawling nation, the Instances’ protection was no vital enchancment over the polls. The Instances’ reporting notably did not anticipate the magnitude of Eisenhower’s reelection — a lopsided victory through which he carried 41 states.

In its closing report earlier than the election, the Instances concluded that Eisenhower would win reelection however would fail to match the sweep of his landslide 4 years earlier. Because it turned out, Eisenhower simply exceeded the dimensions of his victory in 1952, when his profitable margin was 10.5 proportion factors.

The Instances’ protection additionally did not foresee Eisenhower’s state victories in 1956 in Virginia, Oklahoma and West Virginia, and markedly underestimated the president’s help in Connecticut, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Pennsylvania and Texas, amongst different states.

The Instances’ reporting experiment proved an imperfect substitute to election polling, as I mentioned in a analysis paper introduced lately to the American Journalism Historians Affiliation. Within the paper, I outlined “shoe-leather reporting” because the gathering of newsworthy content material by way of in-person interviews, doc searches and on-the-scene observations. The idiom presumes that journalists will pursue fieldwork so energetically as to wear down their sneakers.

“Shoe-leather reporting” has been lengthy celebrated in American media; a extensively printed journalism educator has described the follow as “legendary” and “one in all a only a few gods an American journalist can formally pray to.”

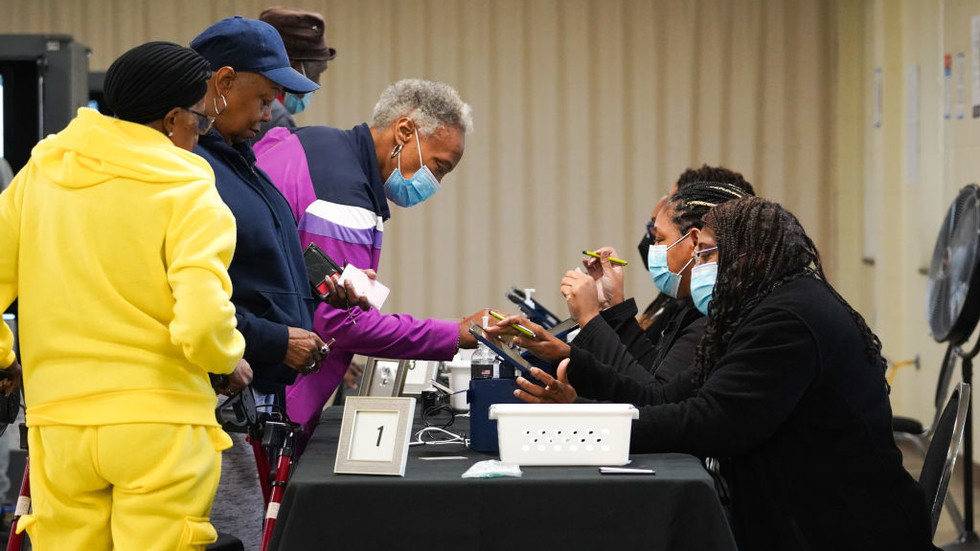

Ban Martin/Archive Images/Getty Pictures

Crises skew projections

The Instances’ experiment in 1956 represents an distinctive case research about each the attraction and limitations of detailed, interview-based reporting as a way for measuring public opinion in a presidential race, particularly when dramatic worldwide occasions happen shortly earlier than the election.

Such was the case in 1956, when the Egyptian authorities seized the Suez Canal, prompting army intervention by Israeli, British and French armed forces — a response that Eisenhower deplored. About the identical time, Soviet tanks have been ordered into Hungary to crush an rebellion towards communist rule and set up a regime compliant to Moscow.

The worldwide crises might have boosted the margin of victory for Eisenhower, an Military basic throughout World Struggle II, in a rally-round-the-president impact.

It was, in any occasion, polling failure that impressed the Instances’ marketing campaign protection experiment.

Eight years earlier, in 1948, the polls, the press and pundits anticipated that Republican Thomas E. Dewey would oust Democrat Harry S. Truman, who had turn out to be president on the loss of life of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945.

However on the power of a vigorous, cross-country marketing campaign, Truman prevailed over Dewey and two minor-party candidates to win.

The main nationwide pollsters of the time — George Gallup, Archibald Crossley and Elmo Roper — all predicted Dewey’s simple victory. Roper introduced in early September 1948 that Dewey was thus far forward that he would cease releasing survey outcomes. Dewey, mentioned Roper, would win “by a heavy margin.”

Truman, who predicted that pollsters can be “red-faced” on the day after the election, carried 28 states and 303 electoral votes. His margin of victory over Dewey, who received 16 states and 189 electoral votes, was 4.5 proportion factors. J. Strom Thurmond of the segregationist Dixiecrat Social gathering carried 4 Deep South states and 39 electoral votes.

Not tied to ‘arithmetic of polls’

Not surprisingly, Gallup, Crossley and Roper turned exceedingly cautious in evaluating the 1952 presidential race, sustaining because the marketing campaign closed that both candidate may win.

Eisenhower, they mentioned, appeared to carry a slim lead however that Stevenson was closing quick. Or because the Instances mentioned in reporting a couple of public gathering of the pollsters shortly earlier than the election: “The ballot takers gave a slight edge within the common vote to … Eisenhower, the Republican candidate, however this was their dilemma: How briskly is … Stevenson, the Democratic nominee, catching up?”

Equivocation didn’t serve the pollsters effectively. None of them anticipated Eisenhower’s sweeping victory — a 39-state landslide.

The Instances didn’t editorially rebuke pollsters for his or her misfire in 1952, however the newspaper’s editors, wrote Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Max Frankel in his memoir, had “misplaced confidence in polls.”

To cowl the 1956 presidential election, the Instances de-emphasized opinion polls in favor of its personal intensive, on-the-ground reporting that targeted on states the place the presidential race was believed to be carefully contested.

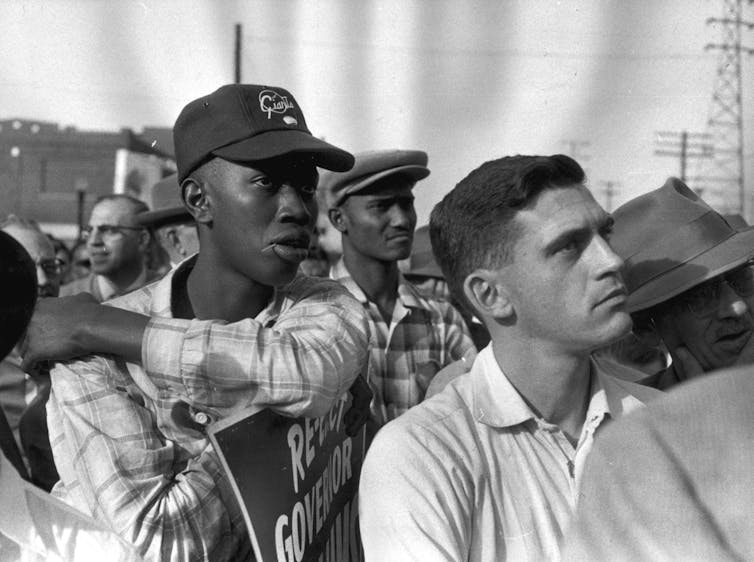

Bert Hardy/Image Publish/Hulton Archive/Getty Pictures

Frankel, who rose by way of the ranks to turn out to be the Instances’ govt editor, recalled being taken off the rewrite desk in 1956 and despatched knocking on doorways “to collect voter sentiment. I drove by way of odd precincts of Milwaukee and Austin (Texas), Arlington (Virginia) and St. Joseph (Missouri), feeding notes” to a colleague on one of many reporting groups.

The groups sometimes spent three days in a state, conducting interviews “with political scientists and policemen, main politicians and bartenders, laborers, housewives and farmers,” the newspaper mentioned.

The Instances described its grassroots reporting as “surveys,” though they weren’t quantitative samples.

“Group members discovered worth in not being tied to the arithmetic of polls,” one of many contributors, Donald D. Janson, wrote in a post-election evaluation for the Nieman Reviews, a journalism business publication.

“The scope and depth of the enterprise was a brand new departure in journalism,” Janson declared.

The method was impressionistic, even idiosyncratic. “Every reporter,” Janson wrote, “was free to evaluate every response, from politician and voter alike, for reliability.”

The Instances printed 36 state-specific preelection reviews, together with 9 based mostly on reporters’ follow-up visits to states the place outcomes have been anticipated to be particularly shut.

In its wrap-up report two days earlier than the election, the Instances mentioned it “appeared uncertain” that Eisenhower’s margin “can be as nice because it was in 1952.” In truth, Eisenhower’s victory in 1956 far surpassed that of 1952; within the rematch, he crushed Stevenson by greater than 9.5 million votes.

The Instances conceded in an after-election article that its teams-based protection “didn’t anticipate the magnitude of the President’s victory,” which it attributed to the Suez disaster and turmoil in Hungary. The crises, the Instances mentioned, “apparently gave the ultimate impetus to the Eisenhower landslide.”

No antidote for dangerous polls

The 1956 experiment in shoe-leather reporting was no rousing success. “There was some feeling,” Janson wrote afterward, “that the Instances ought to keep on with reporting developments and let the pollsters make the forecasts.”

Preelection polls by Gallup and Roper in 1956 precisely pointed to Eisenhower’s victory however overstated the president’s common vote. Eisenhower received by 15 factors; Gallup and Roper estimated his margin of victory can be 19 factors. By 1956, Crossley had bought his enterprise and retired from preelection polling.

Roper declared himself “personally happy” by the result however reluctant to take “any bows for good accuracy.”

Given the unreliability of preelection polls within the late Forties and early Nineteen Fifties, the Instances had ample cause to experiment in looking for a extra exact understanding of common opinion. However as outcomes of the 1956 election demonstrated, shoe-leather reporting was no antidote for the wayward polls.

Supply hyperlink